The Ebb and Flow of Conservatism in Canada: Where will the Tide of Tory Blue Turn Next?

/by Matthew Wiseman

Part 3 of our Canadian election Political History Series. Check out last week's history of the Liberals!

Although Canadian Prime Minster Stephen Harper is currently “under the gun” for a declining Canadian economy and as a result of the Mike Duffy trial, the past eight years has witnessed a resurgence of Tory blue in Canada. In light of this recent success, it is the perfect time to consider the ebb and flow of an intriguing and important political institution in Canadian political history.

The Conservative Party has produced some of Canada’s most well-known and colourful political figures, from the founding Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to Sir Robert Borden to the polarizing names of John Diefenbaker and more recently Stephen Harper. For much of this country’s history, Conservatives have stood as the Official Opposition against a series of Liberal governments. The conservative movement divided in the 1990s, but its unification in 2003 led to Stephen Harper’s victory in 2006. Now, he has a chance to win a historic fourth term as a Conservative Prime Minister. Today, we ask is the party’s new amalgamation of Progressive Conservative and Reform going to be a different story in 2015 than it has previously?

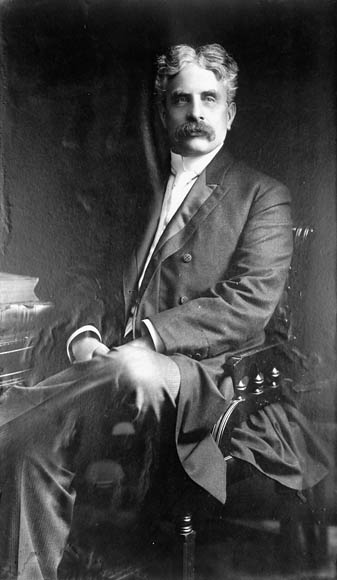

Sir John A. Macdonald via Library and Archives Canada.

The political legacy (good and bad) of Canada’s first and most successful Conservative Prime Minister, John A. Macdonald, is widely recognized by most Canadians, but the nuances of his electoral success often receive little attention. He won an impressive six majority victories in general elections, which came after he had already won two pre-confederation majorities in the United Province of Canada. Considering that Macdonald was only defeated once (after obviously taking a bribe) makes his political success all the more impressive. He died soon after his last election victory in 1891.

After a series of ineffective successors, a Nova Scotian lawyer named Robert Borden rose to leadership of the Conservative Party. After a decade facing Wilfrid Laurier in the House of Commons, Borden revived the moribund party in 1911. He went on to lead the country during the First World War, but not without a great cost to his party.

Sir Robert Borden via Library and Archives Canada.

In the 85 years from the retirement of Sir Robert Borden to the rise of Stephen Harper, the Liberals enjoyed an unprecedented level of success, defeating the Conservatives in 18 of 25 general elections. Much of that success was the result of one decision. When Borden imposed conscription for overseas service in 1917, his loyalty to the Canadian army in France produced a stark political backlash at home. Assailed by French Canadian voters, Borden and his decision to impose conscription greatly damaged the strength of the Conservatives in Québec for two generations. Many viewed his decision as anti-French and the Liberals jumped at the opportunity to pin all Tories as a group of British colonists that were all too happy to send French Canadians overseas to fight and die for the British Crown.

Historians continue to debate Borden’s reasons for the decision. They generally agree that he was not anti-French, though there is no doubt that his decision to impose conscription had grave political implications on French Canadians. In the 25 elections between Borden’s premiership and the rise of Harper, only three times did the Conservatives win more federal seats in Québec than the Liberals did. The five-time premier of Quebec Maurice Duplessis delivered 50 seats to John Diefenbaker in 1958. Elsewise, Brian Mulroney remains the only Conservative leader to have defeated the Liberals in Québec in a federal election since Macdonald did in 1891. Unfortunately, like Macdonald, Mulroney’s government was also plagued with scandals in its final years in the early 1990s. He resigned in 1993 in hopes of allowing his party to escape his unpopularity.

A Brian Mulroney Campaign Poster from the 1980s, via Library and Archives Canada.

Unfortunately, the federal Conservatives descended lower politically on national polls when Kim Campbell succeeded him as party leader. Campbell was a competent politician but faced incredibly difficult circumstances, and the Conservative caucus shrank from 169 to two in 1993 (not including the outgoing prime minister). The party’s previous support in the West and Quebec split between two new parties. The Reform Party took much of the existing Conservative seats in the western provinces, while the Bloc Québecois took all of what Mulroney had built up in Québec, and the Liberals feasted on Conservative votes in Ontario and the Atlantic provinces. The Conservative decline gave rise to a strong Liberal government under the leadership of Jean Chrétien, until Stephen Harper teamed up with Peter MacKay in the early 2000s.

Between 1996 and 2003, the Conservatives underwent a drastic change known as the Unite the Right movement. The movement brought together Canada’s two main right-of-centre political parties, the Reform Party of Canada/Canadian Alliance (CA) and the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada (PC). Both parties were unable to defeat the governing Liberal Party independently, but together a united right could achieve political success. With this aim, Harper and MacKay successfully amalgamated two parties in December 2003. The Conservative Party of Canada has since achieved a level of success that rivals, if not surpasses, that which occurred under the leadership of John A. Macdonald. Any comparison of the sort is certainly far-fetched and somewhat unfair, given the sheer reality of time and circumstance. Nevertheless, as indicated by a strong political record, Harper stands as one of the most successful Conservative politicians in the history of Canada.

A 2003 editorial cartoon depicting Peter Mckay and Stephen Harper along with David Orchard, a PC leadership candidate who opposed the merger between the right-wing parties. Via SFU Library Editorial Cartoons Collection.

According to this brief sketch of Tory history, Conservatives have had a tough run in Canada. Consider that for every three years Liberals have been in power, Conservatives has held office for two. Outside the Macdonald years, Liberals hold a two-to-one margin in this regard. The Liberals have been able to retain the title of Canada’s so-called “natural governing party,” and the Conservatives have been often relegated to the political sidelines. By a similar measure, Canadian historians have published extensively about the trials and tribulations of Tory leadership and Conservative contributions to Canada. Books such as Peter Newman’s Renegade in Power and Denis Smith’s Rogue Tory cast a critical lens, which only recently have books such as Bob Plamondon’s Blue Thunder and Paul Wells’ Right Side Up begun to challenge. Tory leaders find little praise amongst scholars and journalists, except for Macdonald, who himself has come under heated criticism of late for his views and treatment of First Nations. Even the national poll for the CBC program The Greatest Canadian ranked Liberal leaders Lester Pearson and Pierre Trudeau ahead of Sir John A. Macdonald.

When considering the impact of Tory blue on Canadian history, we should look to fundamental political contributions rather than the raw statistics of a bleak electoral record. Tories have led Canadians through tumultuous times and have initiated some of the more far-reaching and formative changes that define the political base of Canada today.

Let’s begin with Confederation. Sure, a business deal by any measure, but one that established a strong political foundation. Macdonald fashioned Confederation to gain power but in so doing, he also strengthened colonial ties to the British Empire and created a nation capable of withstanding a seemingly inevitable political encroachment from the United States. Macdonald’s vision was staggering. Here was an individual, known to his contemporaries as both an avid drinker and strident politician, who envisioned a railway stretching east to west across the northern half of North America. Macdonald wanted to prevent the northward ascension of Manifest Destiny, while giving French- and English-speaking colonist’s access to land that many thought was out of reach.

Using nationalist trade policies and an attack of Indigenous peoples, Macdonald saw his vision through to fruition (or at least a strong start). He instituted a model of governance based on British structure, and at the same time set the Dominion on a path towards economic independence. Over an impressive eighteen years, he achieved six of seven electoral victories and set in motion nationalist policies that became the political backbone of a unified country.

A Conservative campaign poster from 1891, via Library and Archives Canada.

Conservative success diminished extensively following MacDonald’s death in June 1891. Under four successive leaders over a ten-year period, the party failed to gain ground amongst the Canadian electorate. The Tories bounced back in 1911, when Robert Borden earned the premiership of Canada. At the time, the Liberals had pushed a free trade program with the Americans, and Borden successfully campaigned by arguing that any such deal was bad economy for Canada.

The conscription crisis of the Frist World War came to define Borden’s tenure as leader of Canada. During his time in office, the Québec Tory caucus shrunk from 26 to three in the 1917 election, then to zero in 1921. The lasting implications of this political decline are staggering. Consider that, for an entire generation, the Conservatives were not a national political party. Through three elections in the 1920s, the Tories under Arthur Meighen were unable to respond with any significant measure.

The Tories returned to power in 1930 but found no end to their pain. The Great Depression provided the Liberal opposition the ammunition to coin the phrase, “Tory times are hard times.” The Tories made light of a stark situation, however. In response to the global economic crisis, the government of Richard Bennett established the Bank of Canada, credit agencies, farm marketing boards, and the CBC. These transformative institutions remain important symbols and pieces of Canadian life.

Prime Minister Diefenbaker greeting Queen Elizabeth II in 1959, via Library and Archives Canada.

In spite of such drastic reform, Bennett’s government was a victim to the Depression and the Tories struggled through the middle of the twentieth century. In the late 1950s, Ontario-born, prairie-raised politician John Diefenbaker campaigned for the premiership of Canada on the promise of unifying a divided nation. A deep recession had placed Canada in another terrible economic state, but Diefenbaker’s vision of “One Canada” became the backbone of a 1957 electoral campaign that would see his Progressive Conservatives capture a surprise minority victory over the Liberal government of Louis St. Laurent.

Diefenbaker’s tenure was marred with difficult policy decisions, including the sale of Saskatchewan grain and the move to cancel the production of the Canadian-built Avro Arrow jet-interceptor. Yet he successfully instituted the Bill of Rights, an accomplishment that deserves recognition apart from the series of political misfortunes that comprised his time in office. Diefenbaker was a fiery populist who made a name for himself defending the interests of “all” Canadians, but in the midst of recession (and an urban elite arrayed against the party) the populace returned strongly to Liberal red.

In the years following Diefenbaker’s decline, the Conservative party developed a more progressive tone after a series of defeats at the hands of Pierre Trudeau. Conservative Joe Clark’s brief minority government in 1979-80 was humiliatingly defeated after they failed to have enough MPs in the House. The triumphant Liberals handily won the 1980 election.

Signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1992, via Wikipedia.

Only growing support in Québec and the West for the Conservatives secured the election of a majority government for Brian Mulroney in 1984. Under his leadership, Canada’s foreign and domestic policies changed drastically. A party that once campaigned against international commercial exchange established a Free Trade Agreement and opened Canadian markets to external business. Mulroney believed that the time was right to remove protectionist trade policies from Canadian politics, and his efforts in this regard worked to strengthen Canada’s position relative to a rapidly expanding global economy. Yet these same policies opened Canada to financial risk, and Mulroney’s government imploded in its second term.

Not until 2003 did Conservative fortunes rise again under the political maneuvering of Harper and MacKay. The political union of the old Progressive Conservatives and the Western populist Reform Party gave new life to the waning fortunes of both against successive Liberal majorities. With the new Conservative brand, and the popularity of Reform policies in the West and to Ontario Conservatives, Stephen Harper returned the party to power with a minority government in 2006. For the first time, the Conservatives won an election without the support of Québec, winning only 10 of 75 seats in the province. Since then, the partnership of Canadian conservatives has made small inroads, enough to win a majority in 2011.

Stephen Harper, via Library and Archives Canada.

In the end, the rise and fall of the Progressive Conservative Party is certainly much more complex than can be covered in a single blog post. Harper’s Conservatives are often pinned as less progressive than the majority of those who came before, but perhaps conservatism in Canada is today more firm than at any other point in the history of this country. Certainly at least 30% of the country believes the party should remain in power, but that will be for the public to decide in October. In any case, under Harper’s leadership Tory blue has risen to heights not seen in a generation, if not a century. The one difference between Harper’s Conservatives and its historic predecessors is that it does not need support in Quebec, making the future uncertain. Without having to rely on the fickle Quebec vote, the Conservatives have been able to offer a much more solid conservative movement. So where will the party go next? Or perhaps we should ask, what future policy directions will drastically shape Conservative Canada?

Next week we turn to the final of the Big Three Parties, the New Democratic Party.