The Liberal Party of Canada: The Past is Less Important than the Future

/by Geoff Keelan

Part 2 of our Canadian election Political History Series.

The Liberals are one of the most popular political parties in Canadian history. Their seemingly hegemonic power, careful electioneering, and (some) luck, has helped them dominate Canada’s political theatre. Undoubtedly, Liberals have greatly shaped the Canada we live in today. In our initial Political History Series post, we examine the ideological system that has guided Canadian Liberals: liberalism.

First, we should remind our readers that we are not offering complete histories at Clio’s – if only because we have word limits! There are other places to read a detailed history of the Liberal Party. Instead, we want to sketch out points from that history and connect some dots. You won’t see the whole picture here, but you’ll get the outline.

Our story begins on 6 April, 1968, when Pierre Elliott Trudeau stepped onto the stage at the Ottawa Civic Centre to a crowd of cheering Liberal supporters. He had just been elected as leader of the Liberal party, replacing Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson, and was unknowingly ushering in another 16 years of Liberal governance (barring a brief interruption in 1979-1980). In his speech, Trudeau reminded Canadians of why the Liberal Party was so important:

“Liberalism is the philosophy for our time, because it does not try to conserve every tradition of the past, because it does not apply to new problems the old doctrinaire solutions, because it is prepared to experiment and innovate and because it knows that the past is less important than the future.”

Trudeau, a lawyer and long-time political writer, had a precise understanding of liberalism as a political philosophy. He was not simply talking about the ideology of the Liberal Party, but about a philosophical view of the world and government. Today we look back at the history of the Liberal Party to ask, does Trudeau’s statement hold true for the Liberal Party historically? Is it still true today?

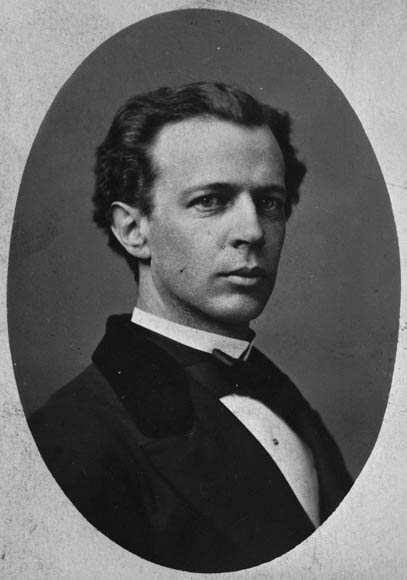

George Brown via Library and Archives Canada.

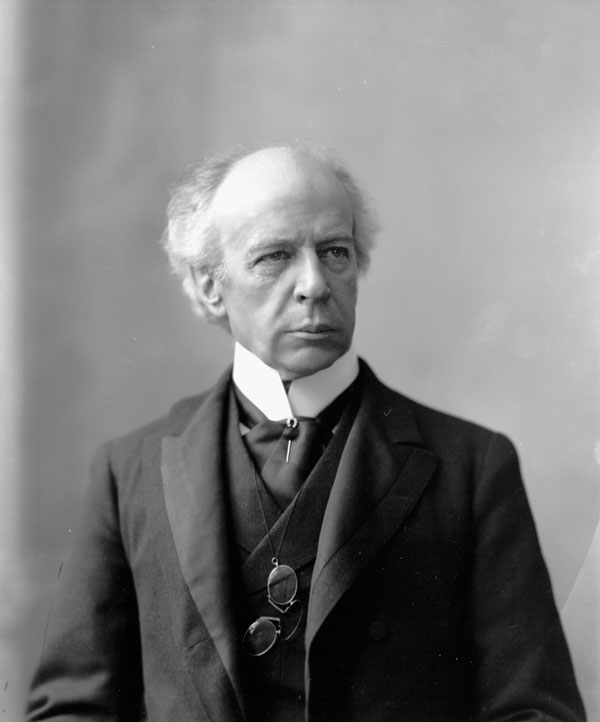

William Mackenzie King via Library and Archives Canada.

The origins of Canada’s political parties lay with the earliest decades of British settlement in Ontario. The young colony had its share of political reformers working towards representative government, that is, representative of the people not the British monarchy. These Reformers were the earliest forebears of modern political parties. Figures such as Robert Fleming Gourlay, later William Lyon Mackenzie and eventually Robert Baldwin, helped lead the early 19th century Reform movement in Canada to achieve representative government (Responsible Government) in 1848. After the union of Upper Canada (Ontario) and Lower Canada (Quebec) created the Province of Canada in 1841, the Reformers worked with their French-speaking left-wing counterparts, the Parti Rouge. By the 1850s, moderate reformers left this informal alliance to join the Liberal-Conservatives (led by John A. Macdonald), while more radical reformers created the Clear Grits led by George Brown, named because they sought members who were “all sand and no dirt, clear grit all the way through.”

In Quebec, the Parti Rouge had emerged as a significant left-wing party in Lower Canada, though one in line with European liberalism. The Rouges, successors to the Patriotes who had rebelled in 1837-38, supported republican government over a parliamentary monarchy, were opposed to Confederation, and were violently anticlerical, putting them deeply at odds with British reformers and Catholic Quebec. They briefly formed a government with the Clear Grits in 1858, but it fell within a day. Its failure pushed more moderate members to consider alternate directions, and they joined the Clear Grits to create the Liberal Party of Canada in 1867. Among them, a former Rouge named Wilfrid Laurier decided to support Confederation and join the Liberals after opposing it for several years as a young law student.

The new Liberal Party formed the opposition against John A. Macdonald’s Liberal-Conservative Party (renamed the Conservative Party in 1873). The Liberals briefly served as government under Alexander Mackenzie after Macdonald resigned over the Pacific Scandal, but Macdonald’s enduring popularity and support in Quebec saw them lose it by 1878. Nor was Mackenzie’s successor, Edward Blake, any more successful at defeating Macdonald. The Liberals could not beat the Conservatives without Quebec support, which required the help of young MPs like Wilfrid Laurier to shift the party away from the virulent anticlerical European liberalism towards British Liberalism (Classical Liberalism). Laurier’s French Canadian heritage and careful acceptance of clerical influence won many Quebec voters to the Liberal fold.

Wilfrid Laurier (1869) via Library and Archives Canada.

Laurier’s liberalism defined the Party for more than half a century. Laurier adopted a Canadian form of Gladstonian Liberalism. It emphasized democratic and representative government, tolerance and justice, the importance of the individual, and free trade. In the Canadian context, Laurier wanted to make sure that the fragile nation didn’t fracture between French and English Canadians. So Laurier specifically did not interfere with the Church in Quebec (garnering enough Quebec votes for his 1896 victory), and believed that Canada ought to slowly but surely disentangle itself from the British Empire, through minor actions rather than grand gestures.

These principles shaped Laurier’s time as leader. He lost his first election 1891 over the issue of free trade, which also eventually defeated him again in 1911. His victory in 1896 united French and English voters who believed in Laurier’s “Sunny Ways” and his capable hand to guide Canada into the 20th century. For the next fifteen years, Laurier used a combination of pragmatism and principle to guide the country through the Boer War, settling the West, the Alaskan Boundary dispute, French-language schools, and many other divisive issues. He maintained a steady support for Empire, if not an enthusiastic one, and I could describe Laurier’s “liberal imperialism” as advocating for its eventual (though not immediate) deconstruction. After the Conservatives regained control of the government, Laurier continued to serve through the First World War as Opposition Leader until his death in 1919.

Wilfrid Laurier (1906) via Library and Archives Canada.

The outbreak and fighting of the First World War had a profound and lasting impact on Canadian liberalism and the Liberal Party. Rising tensions between French and English characterized the war, and Laurier himself wondered if the two peoples would never achieve the unity that he had struggled so hard to build. “I have lived too long,” he wrote in May 1916 as he witnessed a near revolt from Ontario Liberals over restrictive French language schooling, “I have outlived liberalism.” The threat of resignation brought the belligerent MPs in line, but the Conscription Crisis and the 1917 election splintered the party regardless, as many English Canadian Liberals joined Robert Borden’s Unionist war government and French Canadian Liberals stayed loyal to Laurier.

One English Canadian Liberal who stayed loyal was William Lyon Mackenzie King, grandson of 19th century Upper Canadian Reformer William Lyon Mackenzie. His faithfulness and rejection of conscription paid off after the war, when Quebec Liberals helped him gain the leadership after Laurier’s death. King was a shrewd political operator, who recognized the political capital the Liberals had gained by opposing conscription. Quebec, which had also rejected conscription, continued to vote for the federal Liberals after the war. The Conservative’s lingering insistence on a connection to the British Empire in the face of King’s policy of Canadian autonomy did not help their case. As long as King could preserve this bastion of support and gain enough seats in the rest of Canada, the Liberals could win election after election. King was successful and he won the election of 1921 and spent 22 of the next 27 years as Prime Minister, until he retired in 1948.

William Lyon Mackenzie King via Wikipedia.

King inherited the political principles of Laurier, continuing his pragmatic governance in the name of national unity (and Liberal electoral victory). Part of King’s success, particularly in reintegrating the Western Liberals who had broken over conscription, was his ideas about industrial relations and the modern state. His 1918 book, Industry and Humanity: A Study in the Principles Underlying Industrial Reconstruction, was a dense booklet examining the relationship between labour, management, capital, and community (the people). King supported individual freedom as Laurier had, but also believed that the common good sometimes overrode what was best for the individual. In the turbulent three decades of King’s time as Liberal leader, the government often had to intervene for the sake of the “common good” and Prime Minister King undoubtedly helped lay the groundwork for the post-1945 social-welfare state (with help from the Progressive movement – check out our history of the NDP in two weeks!). While King ignored the 1943 Marsh Report that advocated for social security in Canada, his 1945 election did introduce elements of it, and many of its recommendations were eventually enacted under another Liberal Prime Minister, Lester B. Pearson.

Louis St-Laurent via Library and Archives Canada.

When King (finally) retired after the Second World War, Quebec lawyer Louis St-Laurent took up the Liberal mantle. St-Laurent and his Secretary of State for External Affairs, Lester B. Pearson, navigated the international currents of the Cold War smoothly with their own updated idea of international liberalism. In a famous 1947 speech at the University of Toronto, St-Laurent expressed his vision of Canada’s new place in the world. He argued that five principles ought to guide Canadian foreign policy: “national unity, political liberty, the rule of law in national and international affairs, the values of Christian civilization and the acceptance of international responsibility in keeping with our conception of our role in world affairs.” St-Laurent continued to enact new social welfare legislation, while building an international reputation for Canada as a useful ally and negotiator. Under his watch, the Liberals solidified the idea of Canada in the minds of its people as St-Laurent helped shape what historians now term Canada’s post-war “liberal nationalism.”

After twenty-two years in power, St-Laurent and the Liberals lost to populist Tory John Diefenbaker in 1957. Lester Pearson replaced St-Laurent and arrogantly goaded Diefenbaker into another election a year later, resulting in a Conservative majority. Pearson realized that the Liberals had stagnated after two decades in power and renewal was necessary to take on Diefenbaker’s enduring popularity.

In September 1960, the Liberals held an introspective policy conference in Kingston, Ontario, intent on revitalizing the party’s fortunes and deciding new directions for Canada. They detailed that providing adequate (and free) health care would be a Liberal priority, that they would offer better pensions, and expanded other areas of social policy. Four months later in January 1961, a larger grassroots rally of more than 1000 delegates was held in Ottawa. Liberal members confirmed that the new policy was the best direction for the party. The grassroots support for a new vision of liberalism tied the government to helping the individual, a step further than the classical liberal approach of simply protecting the individual.

Lester B. Pearson via Library and Archives Canada.

When Pearson finally returned the Liberals to power in 1963 with a minority government, a readied social policy agenda defined his years at Sussex Drive. At just shy of five years, Pearson’s time in office falls between the forgettable Alexander Mackenzie and Depression-era Conservative Prime Minister R. B. Bennett, but his impact far outweighs the length of his tenure. The introduction of a universal Medicare system and the Canadian Pension Plan were radical changes to the relationship between Canadians and their government. Pearson also continued the Liberal search for national unity, matching rising separatism in Quebec with a new emphasis on Canadian bilingualism, biculturalism and co-operative federalism. It was a heady time for Canadian Liberals and liberal nationalism, which might explain how Liberal Minister Jack Pickersgill could tell journalist Peter C. Newman that, “It is not merely for the well-being of Canadians, but for the good of mankind in general, that the present Liberal government should remain in office.” Arrogant yes, but it speaks to the higher purpose that Liberals imbued upon their electoral victories. Of course Canadians ought to vote Liberals, Liberals were better.

With Quebec on his mind, Pearson brought in a young lawyer named Pierre Elliot Trudeau (alongside other prominent Quebecois) into the party for the 1965 election. Though Pearson again failed to secure a majority in the House of Commons, Trudeau’s indelible charm and success as Minister of Justice helped him win the Liberal leadership after Pearson’s retirement.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1968) via Library and Archives Canada.

On 6 April 1968, when Trudeau won the race for Liberal leader in Ottawa, he was welcomed as a new, progressive face for the party. Instead of immediate change that media and Liberals expected from the left-wing Quebec intellectual, Trudeau drew back from making any abrupt decisions on government policy. Trudeau was as pragmatic as Laurier or King, and immediately quelled fears that he would revolutionize Canada. Of course, that is exactly what Trudeau would do, but it took sixteen years as Prime Minister to do it.

In many ways, Trudeau’s liberalism rejected the old traditions of Laurier, King, and Pearson. Consider his introduction of multiculturalism as an official government policy in 1971 and repatriating the constitution in 1982. The first was a reaction against the nationalist strife that had divided English Canadians and Quebecois during the 1960s (and for our entire history), the second was an affirmation of liberalism’s primary objective: to protect the individual against government encroachment. Combined, they represented a drastic shift from the liberalism first expressed by Laurier nearly a century earlier.

The Canadian liberalism that emerged in the 1970s was first concerned with ensuring social cohesion during a fractious time. Multiculturalism allowed every Canadian to exist under the same umbrella of nationalist identity, rather than only French or English. Next, Trudeau’s government believed that liberalism ought to create structures ensuring future progress of social reform, instead of relying on sometimes-limited political capital. By entrenching the right of the individual and outlining government obligations in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Trudeau bound every future Canadian government to the Charter’s vision of the individual and the state.

So, unlike his predecessors, Trudeau rejected atavistic conceptions of Canadian nationalism as well as social policy based on political capital alone. The Charter guaranteed that all future governments would follow liberal principles, even if they were not Liberals. In a sense, every future government had to be a liberal one after 1982.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau (1980) via Wikipedia.

The divisions that resulted from Trudeau’s time in office may have helped break decades of largely uninterrupted Liberal rule. The Mulroney Conservatives won the 1984 election with the combined support Quebec and the West, both dissatisfied with Trudeau’s policies, and today Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party is a legacy of the western protest movement that began as a reaction to Trudeau.

After the failure of Trudeau’s successor John Turner to defeat Conservative Brian Mulroney, Jean Chrétien assumed leadership and the party adopted electorally popular but neo-liberal views. We will look at the 1990s in a few weeks, but for our history of the Liberals, it is enough to understand that Chrétien seem to take the Liberal brand as an empty vessel to fill with politically acceptable policies that ensured election, rather than the underlying liberalism that shaped previous governments. As a “virtual party,” Chrétien’s Liberals abandoned the top-down paternalistic elitism of King and St-Laurent pushing for government intervention as well as the bottom-up individualism of Pearson and Trudeau’s that demanded social programs.

After the Liberal loss to Stephen Harper in 2006, a parade of “captains” failed to fill the vessel of Canada’s Liberal flagship. Justin Trudeau’s election as Liberal leader in 2013 has perhaps provided some much-needed direction, and maybe some much needed foundations for Liberal policy other than the sole objective of electoral success. As some commentators wonder if the Liberals no longer have a place on Canada’s political stage, voters will have to make a decision on October 19 whether Justin Trudeau’s Liberals are convincing. “Real change” is the Liberal motto in the 2015 election, but it is worth pondering whether that’s change from the Conservative government and NDP opposition, change from the last decades of Liberals leaders, or change like Pierre Trudeau once called for in 1968.

Liberal Members from Justin Trudeau's Papineau riding await his arrival, via Twitter.

Of course, the Liberals probably want you to believe it’s all three, at least until October. The Liberal Party has proven itself adept at transforming its political philosophy to meet the needs of Canadian voters throughout its history, and perhaps they have done so again. It remains to be seen if Trudeau is following his father’s footsteps (for better or for worse), or the “virtual party” of Chrétien. What do you think? How do the Liberals of 2015 compare to their predecessors?

Join us next week for our history of the Conservatives!