Hero or Villain: Sir John A. Macdonald in Recent Canadian memory

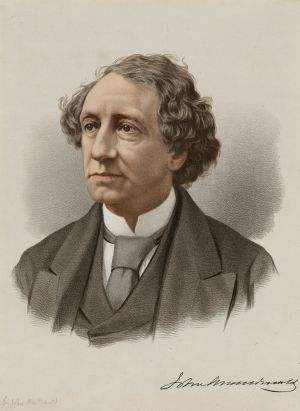

/Much has been made of the 200th anniversary of Sir John A. Macdonald’s birth this past January. You may have heard of the events and speeches in Kingston, the city most associated with Macdonald, or more likely read about Macdonald in the spate of articles debating whether he should venerated by Canadians at all. The argument that Macdonald is the most important Father of Confederation – the man who (some suggest singlehandedly) created our nation – is not new, but its rejection question some seminal myths about Canada.

It has been a fierce debate in the pages of Canadian newspapers over John A. Macdonald’s legacy. Last year, a group of former Prime Ministers marked “Macdonald Day” (his birthday, January 11) by urging Canadians to praise their predecessor and remember Macdonald’s enduring “task of renewing and building Canada.” Macdonald was foremost a nation-builder they wrote and was thus a worthy role model for young Canadians today.

While one rarely expects good history from politicians, they conveniently left out another enduring legacy of Macdonald’s creation of the Canadian nation-state: its abuse of Aboriginal peoples. The day after the Prime Ministers’ message, a controversy erupted over part of the Macdonald Day celebrations where a couple attended in “red face” – that is, white people dressed up as Aboriginals. Underlying the criticism was a new historical understanding of Macdonald’s impact on the Aboriginal peoples who lived in the newly formed Dominion of Canada. As Canada’s territory expanded westward, Aboriginals gradually lost their land to the Canadian government as it was negotiated away from them. They suffered much from the same Macdonald determination that we have traditionally praised. The protest against the celebrations echoed the recent work of historian James Daschuk, whose book Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life laid out in gruesome detail the terrible relationship between John A. Macdonald and Aboriginals.

Daschuk’s work, which ironically won the John A. Macdonald history prize last year, examines the cost of Canada’s expansion and the harsh policies used to secure the plains west of Ontario. The book revealed new research on how the Canadian government “cleared the plains” by allowing famine to diminish their number or force their submission to government demands. Sir John A. Macdonald was one of the primary instigators of these policies. Daschuk’s revelations shed a harsh light on the career of Canada’s first Prime Minister, revealing in detail Macdonald’s now-parochial views on non-Europeans. It is a world and a history that we prefer not to remember.

This year the debate over Macdonald’s legacy was even fiercer. Pundits were eager to join in a debate over Macdonald’s significance to Canada at the expense of Macdonald’s reputation, perhaps since any journalist enjoys a good expose of a political figure alive or dead. The topic was likely popular because it naturally encouraged an emotional response – most Canadians had a visceral reaction to the revelations about Macdonald. All had an image in their minds of the Prime Minister, and the debate forces you to take sides as that image changes or solidifies.

So unsurprisingly, Macdonald was given much attention in the pages of Canadian newspapers in January as we passed over his 200th birthday. The Globe and Mail assembled a team of writer to debate whether Macdonald was a “visionary patriot or hateful embarrassment.” The National Post had similar articles exploring Macdonald the “genocidal extremist” and the “drunk,” though its editorial board used the occasion to remind its reader about the value of all history, good and bad. In The Walrus, Stephen March declared Sir John as “the father of the country we don’t want to be.” The debate spiraled out from these articles into comment sections and onto Twitter and Facebook, as hundreds of Canadians expressed their personal view of their past.

Historians were also involved in the discussion, some writing for the newspapers above while others were involved in the online debate. ActiveHistory.ca ran its own series of posts about Macdonald. They raised topics like Macdonald’s presence in Kingston today, political cartoons’ view of Macdonald, claims of genocide and use of the word Aryan, women and Confederation, famine, concluding with reflection on Macdonald and indigenous people. In February, historian Michael Bliss participated in a roundtable discussion alongside journalist Andrew Coyne and Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Chris Alexander for the Macdonald Laurier Institute. Bliss argued (around the 11-minute mark) that John A. Macdonald set a template for the governance of Canada, and his impact is evident in the “genetic code” of the Canadian politician.

For better or for worse, Bliss is correct. Today, though it has been more than a century since Macdonald last walked the halls of Parliament, politicians are still playing the same game and answering the same questions he did: how do you run a middling power country surrounded by bigger ones, with a divided population? Macdonald’s clever politics that preserved his party’s power repeatedly – even after scandal – remains a guide for any Canadian political party seeking to hold onto government. His National Policy charted a clear and strong direction for the young nation as Macdonald expanded Canada westward for fear of losing the vast territory. In 1891, Macdonald’s last election campaign proclaimed “the old flag, the old policy, the old leader,” successfully making his long serving government a strength rather than proof that change was needed. Alongside his opponent Wilfrid Laurier’s ill-fated decision to promote free trade with the United States, Macdonald won his final election. Laurier eventually won in 1896, but Macdonald continued to shape Canadian politics long after his death a few months after his election win in 1891. Laurier continued Macdonald’s National Policy and westward expansion, unable or unwilling to tack too far off his predecessor’s course. No doubt Macdonald would be impressed with Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s current “sword and shield” politics today.

The furor over Macdonald reveals the temperamental nature of public memory. It can condemn and enshrine, seemingly simultaneously, ideas about the past. Sometimes we don’t even realize the narrow perspective we are taking or its consequences on our remembrance of the past. Discussing Macdonald’s 200th birthday seems a naturally timed topic, as all the links in this post demonstrate, and a fruitful area of history for Canadian scholars and citizens alike. Yet at the same time, it places Macdonald at the centre of Canada’s creation and much of the responsibility for his times. How many other Fathers of Confederation do you know by name? How many have their birthdays commemorated? The concentration on Macdonald as the foundational figure in Canada’s confederation, whether it be fame or blame, offers distorted view of the past. Memory is selective – so the forgotten is as important as the remembered.

Macdonald’s legacy and how we remember him is a lot more complicated than just condemning his treatment of non-Europeans. Years ago, Paul Romney wrote about how historians have “gotten it wrong” with Confederation. Romney argued that the Fathers of Confederation wanted a system where the provinces had a strong voice, rather than a centralized federal system focused on Ottawa. Years of misremembering and misrepresentation had distorted the historical record, subordinated provincial governments, and turned the provincial compact of Confederation into a federal stranglehold. While Romney’s work probably deserves a blog post in its own right, it is interesting to consider it in light of the recent exploration of Macdonald. As the subject of so much praise and condemnation, Macdonald becomes a dominant figure in our memory of Canada’s past. Few wonder whether the Prime Minister had political allies or supporters that helped achieve his great successes and failures. That would take away from his share of the glory (or blame) for his actions.

This Great(or Bad) Man history is the sort of story we should not be telling ourselves anymore – one man does not a nation make. A lot has been written about whether Macdonald is a hero or a villain, but both proclaim his centrality in Canada’s national history. Perhaps Macdonald isn’t important at all, other than a single individual in a historical cast of actors big and small. Ultimately, the vilification of Macdonald seems a strange confirmation of his importance. He still has songs written about him.

German playwright Bertolt Brecht, writing under Nazi rule in the 1930s, wrote a revealing scene in his play Life of Galileo. “Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero,” one character notes and another replies: “Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.” It's clear that we do not need a heroic history, but what, we wonder, could we say about the nation that needs a villain? As Marc Bloch once warned, history is not a court room and historians are not judges or lawyers - we bear witness, we do not indict. The tempest over Macdonald's legacy is a slippery slope and one which ought to make any observer careful. Hero or Villain, Macdonald should not be raised as a spectre of Canada's triumphs or defeats as a reflection of modern Canadian problems. We can only deal with present day mistakes and avoid future ones. Past mistakes should be remembered, as many historians linked today have reminded us, as they cast a long shadow that stretches to the present. But when we shed light on them, we must not let it erase that shadow and the many years between then and now.