Moderate Radicals or Radical Moderates? The History of the New Democratic Party

/by Geoff Keelan

Part 4 of our Canadian election Political History Series. Check out last week's history of the Conservatives!

The New Democratic Party has been a popular – but not popular enough – choice for Canadian voters since its creation in 1961. They have never formed government, though in 2011 they were the Official Opposition with 103 of 308 seats, which was quite the rebound from their disastrous 1993 showing of 9 out of 295 seats. They have traditionally wavered between 15 and 30 seats, sometimes playing a pivotal role in influencing minority governments. For most of their history, they were content to be the “conscience of the House” until their recent electoral breakthroughs.

In our examination of NDP history, we ask how might the first chance at government change the party? Or has it already changed in pursuit of that goal?

The roots of the NDP are Canadian socialists and progressives farmers, though much has changed since the days of these early radicals. Socialism arrived in late 19th and early 20th century Canada but never gained widespread influence as it did in European countries. Historians have argued that a lack of formal education restricted the ability for workers to “educate” themselves, while others point to the power of liberalism and its affirmation of status quo political structures and institutions. Still, socialism was more successful in Canada than in its southern neighbour, the United States. While it failed to create a major party here (at least until 2011), it did succeed in becoming an influential minor party: the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation and its successor, the New Democratic Party. Through them, socialism has drastically affected Canada’s 20th and 21st century.

Progressive Party leader T.A. Crerar, via Canadian Encyclopedia.

In the 1921 election, the two-party system that had dominated Canada since Confederation was transformed when the Progressive Party elected 58 MPs, though they refused to be the Official Opposition despite outnumbering the 49-seat Conservatives caucus. The Progressives had emerged out of western agrarian movement against capitalism, advocating for collective action against grain companies and their monopoly. At their head in 1921 was former Liberal T.A. Crerar, and helped by another notable Liberal, J.W. Dafoe, both of whom had rejected Laurier’s party to join Borden’s Union Government in 1917. Though they refused the role of Opposition as their party was ideologically opposed to the party-system, they also did not want to be tasked with actively undermining Mackenzie King’s Liberal government. Instead, they hoped that Liberals might join the Progressives and gradually remove the party from Quebec’s dominating influence.

Instead, the reversed happened. Crerar quit after failing to unite the party's eastern and western elements. Meanwhile, the Mackenzie King Liberals and the Progressives had similar views, and even almost considered a coalition but King could not accept their more radical position. The Progressives did push King to create old age pensions in 1926, but struggled to dominate the party as planned. Over the next decade, the Progressives were never far from King’s mind as Prime Minister. King himself was progressive, but no radical, and his government relied on the Progressive’s support and coopted their policies.

Internal divisions eventually split the Progressives, as some preferred socialist policies that eliminated all government profit in farming, while others preferred a cooperative business approach. When the Great Depression began in 1929, it devastated Canadian farmers and new hardships intensified lingering divisions. Progressives only won three seats in the 1930 election. They were no longer an effective political force. Some joined a radical group with Independent Labour MP J.S. Woodsworth (the Ginger Group – see our post on fringe parties in a few weeks!) while moderates rejoined the increasingly reformist King Liberals, and others linked with the Conservative Party in 1942 (starting the Progressive Conservative movement).

The failure to change the established system to the benefit of the “working man” (or in this case, the farming man) led them to reorient themselves towards class identities and against the capitalist economy. They believed that the only way to enact real change was to organize the working class against the establishment. At the height of the Depression, this cause seemed more urgent than ever and in 1932 the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was formed. The CCF was a federation of labour, famer, and socialist groups determined to reorganize Canada’s economic system.

Picture of CCF founding in 1932, via Library and Archives Canada.

At their first national convention in Regina, the CCF released the fourteen point Regina Manifesto that outlined their political positions and chose J.S. Woodsworth as their first leader. They aimed to replace “the present capitalist system, with its inherent injustice and inhumanity, by a social order from which the domination and exploitation of one class by another will be eliminated.” Ultimately, their goal was to “[eradicate] capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Cooperative Commonwealth.” In order to satisfy the socialist elements of the party (centered in urban Ontario) and the farmer radicals, the new party promised revolutionary change by non-revolutionary means. The partnership between farmers and labour was a tenuous one, and the party’s center slowly shifted eastward away from its agrarian roots.

The implicit threat the CCF offered rippled through Canada’s political arena over the next two decades of Liberal government. In their first electoral foray in 1935, the CCF finished fourth with seven seats, behind the prairie populist and Alberta based Social Credit Party with 17 (another fringe party, at least federally), though the CCF had more than double their popular vote. Despite their poor showing, it was the lasting strength of the CCF in the federal arena that began the transformation of Canada’s two party system. The back-and-forth struggle between Liberals and Conservatives continued, but the CCF’s capitalist critique forced the Liberals to react. King slowly enacted more progressive policies regarding labour, housing, agriculture, and civil liberties. He believed that the Liberals could enact much of the CCF’s legislation, but without resorting to socialism.

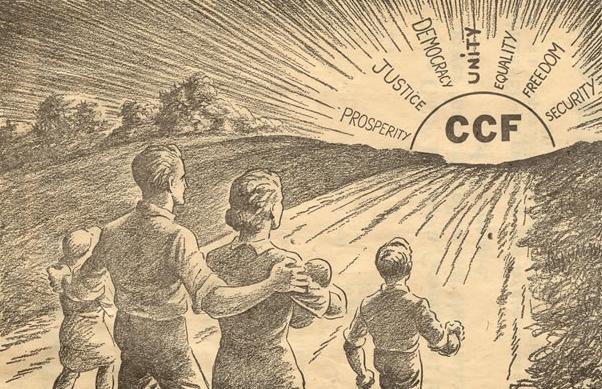

An election ad for the Saskatchewan CCF, via USask's Online Exhibit.

The CCF experienced diminishing returns by the late 1950s. Two decades of Liberal rule and a decade of post-war prosperity had improved the standard of living in Canada. The heavily anti-communist atmosphere of the Cold War engendered suspicion of the socialist party. The 1956 Winnipeg Declaration watered down their original manifesto from Regina, but still affirmed that capitalism required control through social planning.

Tommy Douglas in 1963, via Toronto Public Library.

The broadening of the CCF platform to attract less radical middle-class Canadians is a familiar turn for us in 2015. After Diefenbaker’s majority in 1958, where the Conservatives won all but five of the 70 ridings in the traditional CCF heartland west of Ontario, the pressure to moderate their views increased. The CCF begun emphasizing public control rather than outright public ownership of the economy. Calls for a new party with less direct connections to socialism and labour unions eventually led to the formation of the New Democratic Party.

The New Party Declaration of 1961 established a new federal political party, soon under the leadership of Saskatchewan’s long serving CCF Premier, Tommy Douglas. Historians have argued with much debate whether or not the creation of the NDP was a radical shift or a natural progression from the CCF. Had they turned a socialist movement that sought systematic transformation into an organized party accepting the status quo? Or merely adapted to the best practical way to achieve their goals?

Regardless, the direction for Canada’s new democratic-socialist party proved fruitful. Advocating for “new methods of social and economic planning,” the NDP evoked an economic nationalism to rally Canadians to support their reforms. State intervention, state ownership, and removing foreign control of the Canadian economy were core issues for the 1960s NDP. Under Tommy Douglas, the NDP regained the political capital they had lost as the CCF as their seat count steadily increased. In the 1962 election, they won eight seats out of 265, and 17 a year later when Lester Pearson became Prime Minister. In 1965, the NDP won 21 seats and 22 in the 1968 election.

Tommy Douglas stepped down after a decade as leader in 1971. Under his leadership, the new party had greatly increased its share of the Canadian vote. Alongside Lester Pearson’s minority government, Douglas helped create Canadian Medicare and the Canadian Pension Plan. David Lewis, Douglas’ replacement as leader, led a much a stronger NDP than the one created a decade earlier. The party had successfully shifted from socialism to “democratic socialism,” an acceptance of political liberalism and Keynesian economics, proposing economic intervention and state welfare, and a commitment to social equality. They established themselves as a viable third party in the House of Commons.

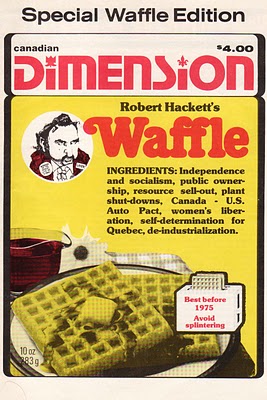

Cover of Canadian Dimension featuring the Waffle, via Next Year Country.

The shift away from more radical left-wing perspectives was not without its critics. In 1969, a subgroup formed within the NDP: the Waffle movement. Drawing from the “Old Left” of the CCF and the “New Left” of the NDP, the Waffle demanded a socialist Canada independent from foreign control. Between 400 and 500 NDP members signed the Waffle Manifesto, arguing that the NDP had forgotten their goal to transform society. One of their leaders, Jim Laxer, was a serious contender for NDP leadership in 1971. Laxer ran against David Lewis, gaining 40% of the vote on the final ballot, but after Lewis’ victory, the new leader subsequently disbanded the “party within a party.” Despite its failure, the Waffle movement still shaped NDP policy in the 1970s and 1980s. Lewis helped Pierre Trudeau’s 1972-74 minority government nationalize parts of the economy with the creation of Petro Canada.

Ed Broadbent, the popular NDP leader of the 1980s, helped write the manifesto. He replaced Lewis in 1975 and would lead the party until 1989. A year earlier, with help from the NDP, the Conservatives under Robert Stanfield forced Trudeau’s minority government into an election. They lost and Trudeau regained a majority, and Lewis even lost his own seat. He resigned and Broadbent replaced him as a new era began for the NDP. Over the next fourteen years, they reached the peaks of their popularity with Canadian voters (at least until 2011).

Part of this was a result of new policy changes. At their 1983 convention, the NDP shifted their policy left-ward with the release of the New Regina Manifesto. Influenced by the Waffle movement, the new policy platform updated the party for the 80s. It made environmentalism an important concern, addressed gender inequality and discrimination, and affirmed Quebec’s status as a “distinct society.” Broadbent’s direction had its opponents in 1983, who worried that the turn would alienate Canadians. Only a speech by the then 79-year old Tommy Douglas helped buttress support for Broadbent as former Saskatchewan Premier Allan Blakeney and Alberta NDP leader Grant Notley raised their discontent with the party’s new policy decisions.

Ed Broadbent (centre) after being elected NDP leader in 1975, via Canadian Encyclopedia.

Fortunately for Broadbent, these developments proved immensely successful in the 1980s. In the 1984 election against John Turner and Brian Mulroney, the NDP won 30 seats – just 10 behind the 40 seat Liberal opposition. In the 1988 Free Trade election, the NDP won their highest seat count ever of 43 seats, though were now 40 seats behind the second place Liberals. On the other hand, the NDP did secure 20% of the vote, an increase from their average under the CCF and before Broadbent became leader. A larger share of Canadians, who did not shy away from supporting its new left policies, welcomed the NDP alternative to 1980s neo-liberalism. It was not however, enough to win government or even Opposition status.

The 1993 backlash against the Conservative government did not help the perennial third party; they won only 7% of the vote and were reduced to nine seats behind the new Bloc Québecois and Reform Party (the Conservatives finished a dismal fifth with two seats). Now under the leadership of Audrey McLaughlin, the party floundered for the next decade. Alexa McDonough improved the party’s fortunes slightly in the late 90s, but its recovery did not truly begin until Jack Layton’s selection as leader in 2003.

Since his death in 2011, Jack Layton has taken on somewhat mystical proportions in the minds of Canadians (and certainly NDP supporters). He continued banking on the leftward direction for the NDP against an increasingly weak Liberal government. The 2004 Liberal minority government put the small NDP caucus in an influential position as they controlled the government’s survival. The 2005 Budget was influenced by Layton, who wrought concessions from the Liberals in exchange for NDP support in Parliament. Removing that support in late 2005 caused the 2006 election, bringing Stephen Harper and the Conservatives to power.

Ed Broadbent and Jack Layton at a New Democratic Party rally during the 2008 federal election, via Wikipedia.

Layton’s NDP continued to perform well as Liberal support diminished. In 2008, they won 37 seats, nearly beating Broadbent’s 1988 record. However, the May 2011 election was a breakthrough. Jack Layton became leader of the opposition with a 103-seat caucus, 59 of which were in Quebec. Though Layton died of cancer in August, he had led his party from the forever third party to an actual contender for government.

As had happened many times before, Layton’s death caused much reflection in the NDP. What would be the new direction of the party? In 2012, NDP membership chose Thomas Mulcair as their new leader over Brian Topp. The division was a clear one – Mulcair was a former Quebec Liberal, while Topp was a NDP strategist close to Layton who had the backing of Ed Broadbent. The party faced a decision as to move left or right on the political spectrum, and by choosing Mulcair they shifted right. The 2013 Convention affirmed the new direction of the party as it removed the word socialism from its constitution.

Jack Layton in 2011, via Wikipedia.

In many ways, the history of the NDP is a balance between radicalism and status quo. Their history is marked by debate between moderate radicals and radical moderates. In their quest for political success, they have often struggled between these two sides. The original CCF formed from Progressive radicals, while the creation of the NDP three decades later was a decision to reject the transformational goals of the CCF, but accept their values. That decision allowed them to flourish as a third party and as the “conscience of Parliament.” While Layton was inordinately successful in 2011, much of that victory lies with Quebec turning away from the Bloc Québecois, rather than Canadian acceptance of NDP policy. The rightward lurch with Mulcair may be what’s needed to form the first NDP government in Ottawa, just as the 1961 formation of the NDP was required to survive as an influential political party. The Mulcair NDP have so far proven extremely successful with their new left-of-centre-but-not-too-far-left position, but the party’s more radical elements often wonder at what cost. The future will reveal whether it worked and how far NDP faithful will allow it to influence party policy.