Necessity, Ideology, and Federal Party Leaders

/by Trevor Ford

Part 7 of our Canadian election Political History Series. Check out last week's post on fringe parties!

Since 1867 Canada has had 22 Prime Ministers in Parliament. Each party leader has brought their own unique vision to their party that sometimes hindered and other times helped their pursuit of power in Ottawa. In that same time there have been multiple third parties that have taken a completely different path from that of the ruling parties to gain the much coveted Official Opposition status. And of course behind every third party was a dedicated leader with vision and ideology that shaped their party. Yet the question is how much do these visions and ideologies affect actual federal policy?

Newly minted Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2006 addressing party faithful, via Wikipedia.

Political commentators have often noted that Prime Minister Stephen Harper represents one of Canada’s most ideological Prime Ministers. Case and point are a number of his more conservative actions such as scrapping the long gun registry, the long-form census and his party’s hardened stance on crime (although this latter point has been consistently held in check by the Supreme Court). His opponents have argued that the Prime Minister’s ideological vision is changing the Canadian social fabric.

Thus the argument goes that the Conservatives have offered a more right-wing ideological driven mandate than any previous federal governments. However there are several problems with this argument.

When the Great Recession hit in 2008, the Conservatives did not implement a campaign of austerity that was carried forward in places such as Britain, France, and other EU nations. Instead, the Conservatives launched a massive public spending platform that sunk billions of dollars into infrastructure spending and bailing out weakened Canadian industries. This was hardly the Conservative vision laid out by Stephen Harper only a couple years earlier. Fiscal conservatism and less government expenditures were supposed to be the Conservatives legacy. This is something that they have heralded since unifying the right in 2003. Even Prime Minister Harper’s MA Thesis in Economics essentially called on the government to never use a stimulus package to rescue an ailing economy. His subsequent stimulus actions in many ways disenfranchised traditional fiscal Tories who saw this turn around as equal to a surrender of Conservative values and an establishment of one of the largest deficits in Canadian history.

Lester Pearson occupying his new office after his election win in 1963, via Library and Archives Canada.

Likewise the Prime Minister’s seeming willingness to give up on Senate reform and Employment Insurance reform also seemed to go against his supposed conservative ideology. Are the Prime Minister’s opponents exaggerating his ideological positions? Perhaps not. Prime Minister Harper may have strong ideological convictions but the political reality of Canada is that elections require a focus on balancing regional and identity politics – usually at the expense of ideology.

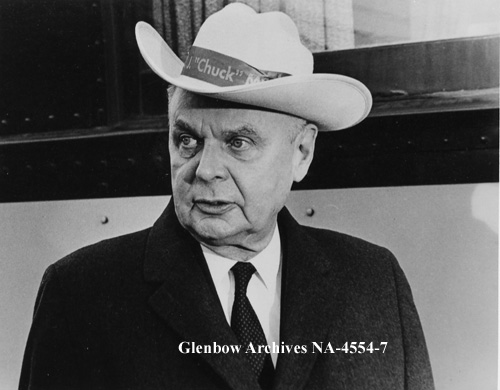

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker campaigning in Calgary, via Glenbow Archives.

Many of the most important perceived ideological steps taken by various Prime Ministers in modern Canada have been mistakenly attributed to party or leader ideology. Take Prime Ministers John Diefenbaker and Lester Pearson’s implementation of the welfare state that began by helping cover the costs of healthcare in the early 1960s. Since they were from two separate political parties and they themselves were vastly different individuals, it is hard to imagine that both were driven by an ideological position to accomplish the same goal. Their successors moved in the same general direction. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau further expanded the welfare state in his tenure and instituted monumental legislation such as establishing the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney also continued to deal with constitutional issues and enshrined multiculturalism in Canada, despite both being legacies of Trudeau’s era. How much were these actions based on the leader’s ideological beliefs?

Perhaps these vast changes to the Canadian political framework were simply a reaction to provincial ideological movement than to any one leader. If it is difficult to adhere to ideologies at the federal level, then where do they thrive? Despite the drastic transformations made by Prime Ministers, many profound changes in the Canadian political landscape begin at the provincial level. Sometimes these provincial rumblings have transcended into the federal level but for the most part they emerge through Canadian Premiers changing the political layout of their provinces and Canada. The Prime Minister then reacts to these changes.

Tommy Douglas in 1945, via Wikipedia.

A good example is how the welfare state began. Future federal NDP leader, but then CCF Premier of Saskatchewan, Tommy Douglas led the charge to introduce Medicare in the province, an early form of medical insurance for all Saskatchewanians. Although there were concerns by doctors, economists, and political rivals to whether this feat was even possible, Premier Douglas strove ahead. This action of government-subsidized health care was one of the first steps towards an expansive welfare state in Canada. At the provincial level, the ideology of the welfare state proved to be successful. Successive federal governments consequently enacted similar legislation. Both Prime Ministers John Diefenbaker and Lester B. Person oversaw the expansion of offering federal funding to provinces that choose to start a form of Medicare.

Likewise some of the more profound changes such as the Constitution Act of 1982 and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988 were attempts by the federal government to satisfy regional differences and check identity disaffection. The last great political battle of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was the patriating of the Canadian constitution and entrenching the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedom. This too was a direct reaction to provincial independence advocated predominantly by Quebec and to a lesser extent Alberta and other provinces. Equally, Mulroney’s 1988 Multiculturalism Act was another step to stem provincial identity issues and regional discontent by recognizing Canada’s ethnic mosaic.

Ralph Klein, Premier of Alberta, via Canadian Encyclopedia.

One example that has affected this upcoming election, balancing budgets and deficits, first emerged as an ideological position in Alberta during the 1990s. Ralph Klein had been elected Premier on the idea that Alberta needed austerity to get out of a massive debt that had accumulated over the years of oil glut. Premier Klein slashed government spending by over 20 per-cent and lowered corporate taxes creating the “Alberta Advantage.” This, along with an improvement in crude oil costs, helped Alberta climb out of a massive deficit under Klein’s tenure. His provincial ideology would later permeate across Canada as the federal governments’ attempts to balance deficits became major political priorities for the first time in a half-century, beginning with Prime Minister Jean Chretien’s Liberals and his successor, Paul Martin.

In 2015, the election debates and speeches have been heavily focused on deficits and balancing the economy. Among political pundits (and likely the general population) it is assumed that the supposedly entrenched Conservative ideology of balanced budgets has led Stephen Harper to campaign on eliminating deficits, while forcing other parties to respond. Thomas Mulcair and the New Democrat Party have stated that they will balance the books no matter what, which is definitely a change in fiscal ideology from previous NDP positions under Jack Layton, Audrey McLaughlin, and Ed Broadbent. Meanwhile the Liberals under Justin Trudeau have argued that small deficits are needed, even though just two months ago Trudeau called for no deficits. Prime Minister Harper has led this ideological charge in hopes of winning the election this year, but it is important to understand this change as part of an ideological shift that began in Canada with Premier Klein’s election in 1992. (And itself is part of global political change solidified in the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan or Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.)

So what does all this mean? How can a voter understand that despite the fact that the Conservatives have been ideological opposed to deficits, they have ran six straight deficits since being in office. Is the federal government truly devoid of ideology, and has Prime Minister Harper been running on an ideology of rhetoric? Not quite. Rather, it means that regional differences have acted as a check on federal leader’s ideological ambitions. Instead, it is at the provincial level that ideological differences have taken shape as more homogenous provincial populations have lead political parties to differentiate themselves via ideological policies or reginal policy balancing. In Ottawa, ideology is usually sacrificed for national concerns such as unity, economic equality between regions, or future electoral success.

The federation that forms Canada has always had many different regions, cultures, and identities – and only has only become more diverse in the century and a half since its forming. These play powerfully on the federal government that is supposed to represent all Canadians. Prime Minister Harper and Mr. Mulcair’s current passion for deficit crushing is an acceptance of a provincial ideology that they have taken on as their own. Just like Mr. Trudeau’s deficit inducing plan can be taken right out of the Ontario provincial Liberal party’s ideology. Each have had “test runs” so to speak, where their success has been proven in far more accommodating environments. So in the end, how much does a federal leader’s ideology play out at the federal level? Apparently, not that much.