Outside Looking In: Canada's Fringe Parties

/by Geoff Keelan

Part 6 of our Canadian election Political History Series. Check out last week's post on negative political advertising!

Although only the Liberals and Conservatives have ever formed government in Canada, our history is riddled with other parties throwing their hats into the ring. Sometimes, these fringe parties have an impact on Canadian governance, but mostly they sat on the sidelines. This week, we discuss some of the “fourth parties” that have sat in the House of Commons.

Fringe Parties have been present in Canadian Parliament since it first formed in 1867. In Canada’s first federal election, the Maritimes’ “Anti-Confederate” party won 23 seats in the House of Commons. Their goal was to separate Nova Scotia and New Brunswick from the new federation of provinces, but Britain refused their request to secede. Eventually, its members joined with the established Liberal or Tory parties, but they are an auspicious start to Canada’s first continent-wide foray into parliamentary democracy. When the periphery vehemently disagrees with the centre, parties on the fringe emerge in strength!

Over the century and a half of parliaments since then, there have been numerous other fringe parties. Too many to name here so instead we are concentrating on a few notable examples. The Prairies have resulted in a multitude of fringe parties, some that had lasting power and others that withered away according to fickle voter preference. Understandably, the Prairies have traditionally felt like outsiders from Canada’s “core” in Ontario/Quebec, leading to smaller parties gaining footholds there.

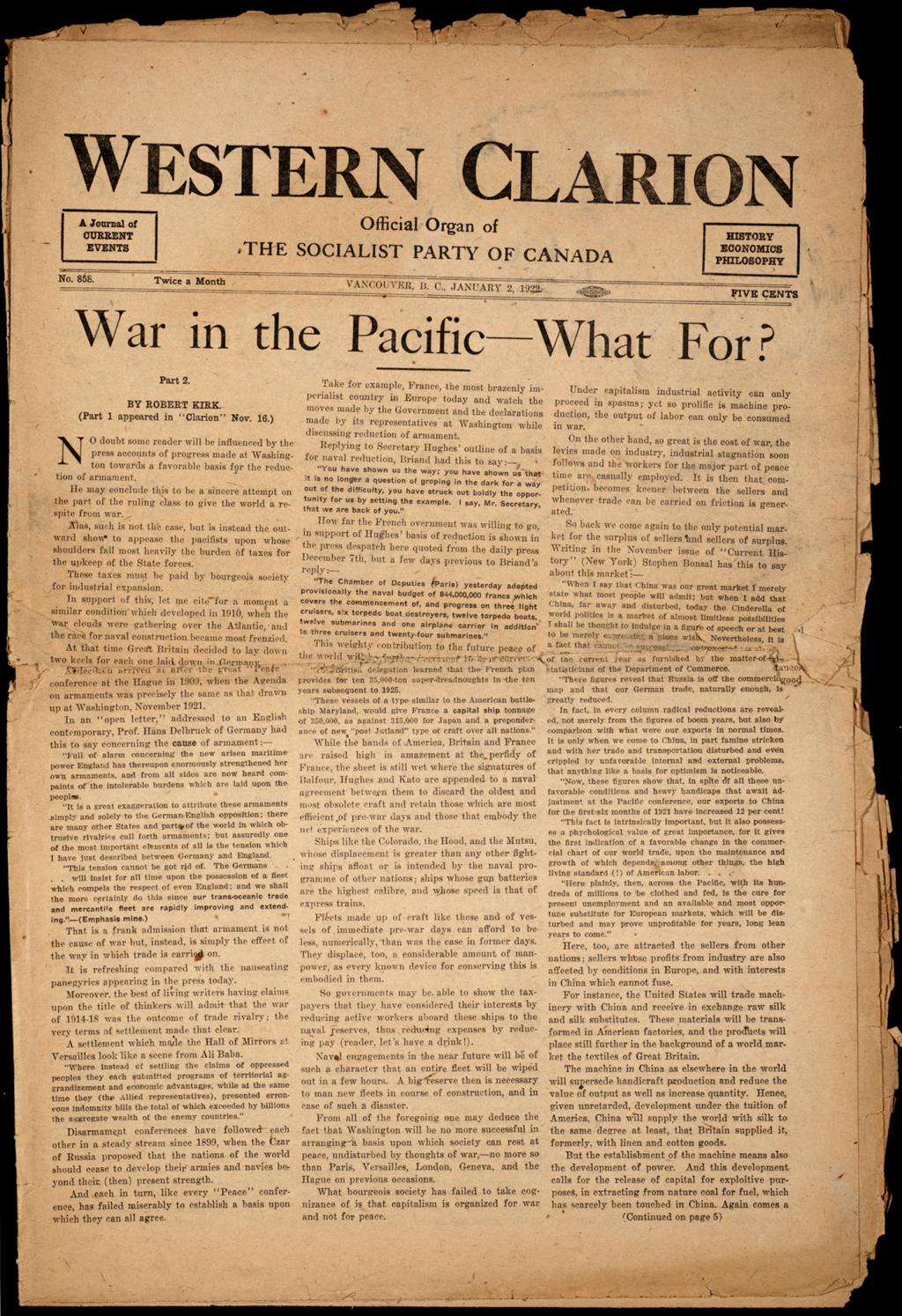

The Western Clarion, Canada's Socialist newspaper, via Wikipedia.

Vancouver Socialists in 1903 via wordsocialism.org.

One of the earliest examples of this was the rise of socialism, though it had a base in Ontario as well. Socialism emerged as a strong political force in Canada only in the last decade of the 19th century, but never achieved great strength here. The revolutionary knowledge of Marx and Engels garnered meagre support in the early 20th century. While the formation of the Socialist Party of Canada (SPC) in 1904 helped bring together disparate provincial organizations, their hardline dogmatic positions led to a break and the creation of the Social Democratic Party of Canada (SDP) in 1910. The Socialists wanted outright revolution, while the Social Democrats tended to support more likely democratic reforms, since revolution seemed far off. The two each numbered around 3,000 members at the eve of the First World War and both suffered from government suppression during the conflict, especially after the Russian October Revolution.

The rise of the Bolshevik state in Russia sharpened the Canadian government’s focus on potential radical elements at home. Lenin and his followers had declared the world’s first proletariat revolution in October 1917, and demanded workers around the world follow their example. The call echoed throughout Canada and increasingly all shades of labour and socialist supporters were targeted as potential home-grown revolutionaries. Out of the turmoil in the last years of the war and afterwards (such as the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike), the Workers Party formed – the legal wing of Canada’s Communist Party. Effectively under the control of the new Soviet Union, the divisions between far-left socialists over whether or not to support the new communist movement divided them even further. (For the curious, Ian Angus’ SocialistHistory.ca offers many documents and essays on Canadian socialists.)

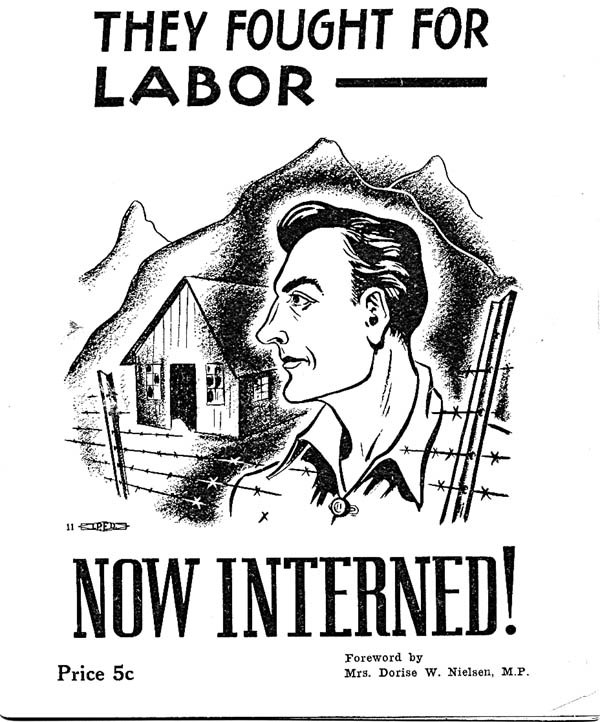

A 1941 Pamphlet, via socialisthistory.ca.

It is no surprise that socialists did not elect a great number of members to Parliament. While they had varying degrees of success in provincial elections, their vote share in federal elections rarely exceeded a handful of candidates or more than 1% of popular vote. Their own internal divisions fractured the party, as did their revolutionary rhetoric and consistent demonization. One MP, Fred Rose, was elected to the House of Commons in a 1943 by-election and again in the 1945 election. However, Rose was revealed as a Soviet spy by the defector Igor Gouzenko in the opening act of the Cold War, allegedly leading an impressive 20-person spy ring in Canada. Rose was eventually arrested and expelled from the House of Commons and stripped of his Canadian citizenship. As we discussed last week, other socialists helped form the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, which at least proved somewhat electorally viable.

The new leader of the CCF, J.S. Woodsworth, had been one of the most prominent and vocal fringe elements of Parliament. Although he was an independent Labour candidate, he sat with the Progressive Party. In 1924, radical Progressives split off from the party in opposition to the party’s cooperation with Prime Minister Mackenzie King. The group of MPs was named the Ginger Group, since ginger was sometimes applied to an old horse to encourage new life. Woodsworth and his loose coalition of MPs believed that new energy could push the progressive movement towards its goal of systematic reform. Unlike other MPs, they felt they owed their seats not to the party under which they ran, but to the constituents who had voted them in to office. Thus, they preferred to be an independent group rather than a formal party and (largely) unsuccessfully pushed for change.

While they helped pass old age pensions, they never gathered enough influence to achieve their greater goals. Eventually, they joined other labour and socialist supporters to form the CCF. With the trauma of the Great Depression and a more solid base nationally, they passed from “fringe” party to “third” party, replacing the 1920s Progressives.

J.S. Woodsworth via Wikipedia.

By the 1930s, western Canadian populism continued to support for the CCF in some regions, but a more active and long lasting strain also emerged. The Social Credit movement would dominate western politics for decades.

Social Credit was a political philosophy imported from Britain, where C.H. Douglas theorized that government control of financial credit could allow a society to reach its full potential. Democratic control of credit allowed individuals to realize their purchasing potential, and the government ought to supplant individual income to create a democracy of consumers served by producers.

Social Credit governments were remarkably successful in Canada, notably in Alberta where it fused with fundamentalist Christianity under William Aberhart (also known as Bible Bill). In the midst of the Great Depression, Aberhart believed that social credit was the solution to the province’s economic problems. Aberhart became Premier from 1935 to 1943. Even though the federal government never legally allowed a social credit system to exist, it did not hurt the enduring popularity of the party, and the Social Credit Party led Alberta won every election in the province until 1971. A Social Credit government also came to power in British Columbia from 1952 to 1972 and 1975 to 1991.

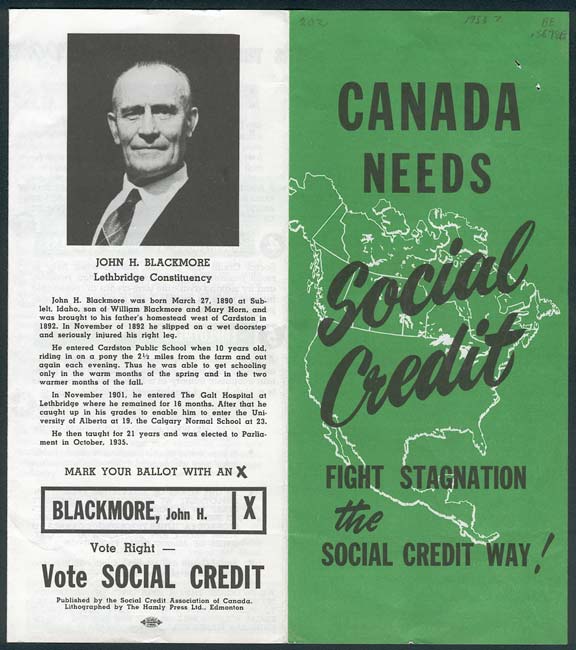

Pamphlet for Social Credit leader John H. Blackmore, via Glenbow Archives.

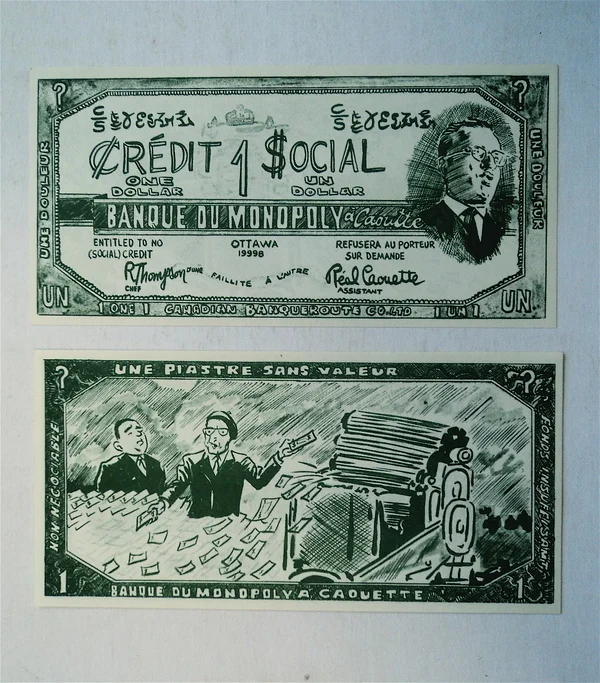

A "Social Credit Dollar," mocking their economic plan.

Federally, the party was far less successful. They won 17 seats in the 1935 election under the leadership of John H. Blackmore, but could do little to sway Mackenzie King’s majority government. The party slowly dwindled until they lost all their seats in the 1958 Conservative victory. Strangely, a few years after the party’s western base was eliminated, it won 25 seats in Quebec in the 1963 election. The Quebec branch, the Ralliement des créditistes du Canada, was led by Réal Caouette. They demanded that Caouette became leader of the national party as well, but resistance from western Social Creditists to a French Canadian Catholic leader caused the party to split along linguistic lines.

Neither side profited from the divide, as both gradually weakened. Caouette’s resignation and death in 1976 spelled the end for the French branch of the party, while the English side had already disappeared in the 1968 election. Their six federal seats won in the 1979 election helped support Joe Clark’s federal government and their refusal to support the budget helped bring down Clark’s government. Unfortunately, they lost all their seats in the ensuing 1980 election. In Quebec they were gradually subsumed into a larger separatist movement, while in the West they emerged federally as the Reform Party a decade later.

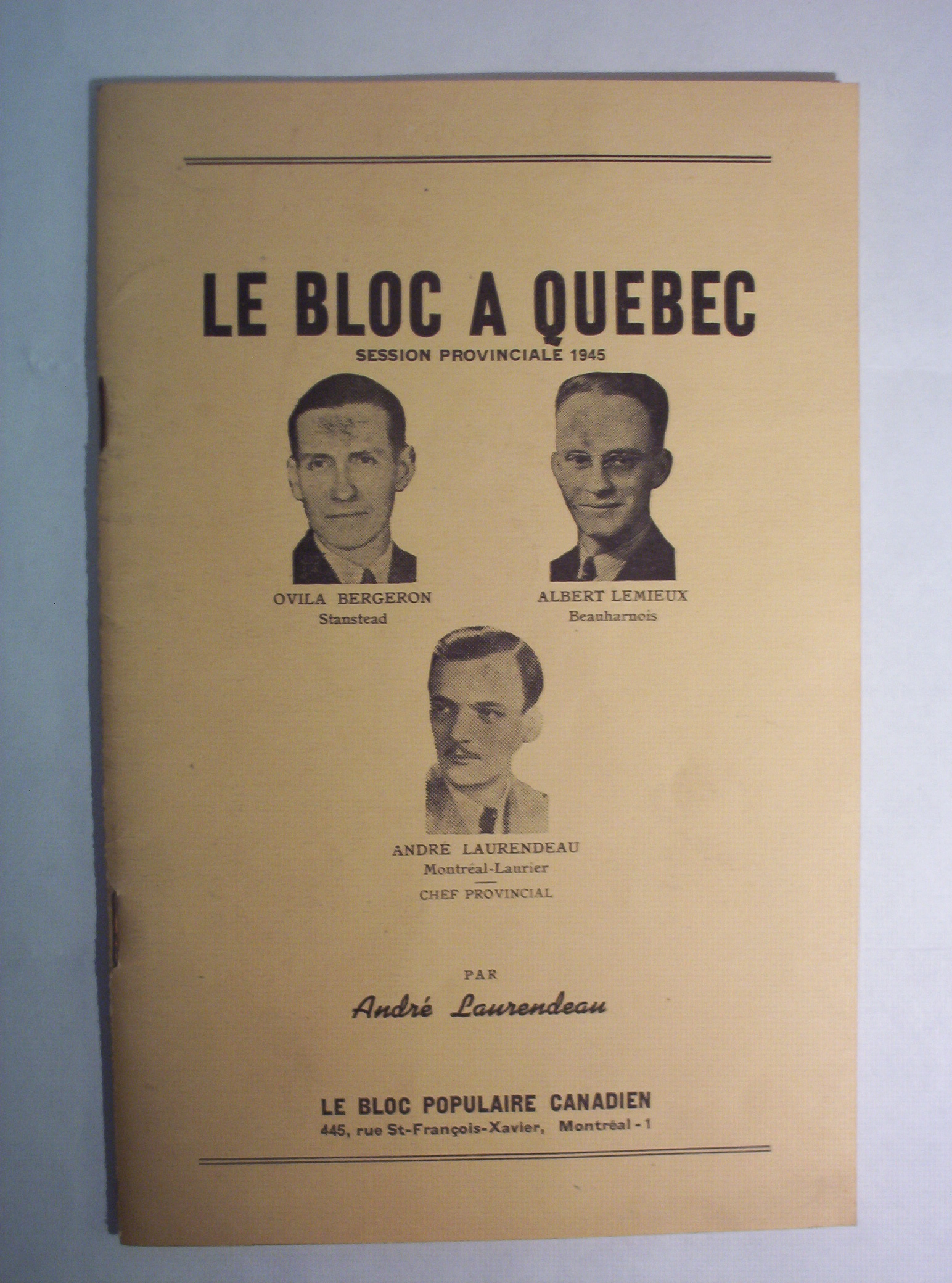

A 1945 Bloc Populaire pamphlet, via Wikipedia.

The Quebec Social Creditists are just one example of Quebec’s tendency to elect fringe MPs. Much like the Prairies, Quebec has been on the periphery of Canadian power enough to elect non-mainstream parties. Perhaps the most famous is the Bloc Québecois, elected to Opposition in 1993, thus arguably successful and influential enough that it would not be considered a fringe party today (though maybe Clio’s Current 2050 will). One important predecessor to the separatist party was the Bloc Populaire, a protest party from the Second World War.

The Bloc formed because of the conscription crisis during the Second World War. Quebec, remembering the First World War a generation earlier, rallied around opposition to forced military service. At the federal level, Maxime Raymond led the party after he and two other MPs defected from the Liberals to form a Bloc Populaire in Parliament. The Bloc combined an older French Canadian Catholic nationalism (akin to that of Henri Bourassa) with a newer brand of modern secular nationalism, epitomized in the rise of André Laurendeau. They demanded an end to conscription, as well as provincial autonomy for Quebec, and equality between Canada’s English and French speaking peoples. The end of the war and conscription removed the primary vehicle for the party’s purpose, and the party became defunct by the late 1940s.

Some of the more popular fringe parties that are still active today emerged in the last half century of Canadian politics. The communists and socialists from the first half of the 20th century continued to suffer from divisions. The 1970 formation of the Communist Party of Canada (Marxist-Leninist) occurred over the decision to support China or the Soviet Union vision of communism split its adherents again. The new group did not improve their political fortunes.

A far more popular though equally unsuccessful party was the Canadian Rhinoceros Party. Founded in 1963 by Quebec doctor Jacques Ferron, its popularity soon spread through the nation. The name was chosen because politicians were generally known to be “thick-skinned, slow-moving, dim-witted, can move fast as hell when in danger, and have large, hairy horns growing out of the middle of their faces.” Reflecting the behaviour of more than a few mainstream parties, the Rhinos promised to keep none of their promises every campaign, a move that attracted hundreds of votes across Canada. Some of their policies have included naming lottery winners to the Canadian Senate, demanding that Queen Elizabeth make her seat of power Buckingham, Quebec, and replacing every small business with a very small business (and many more). The peak of the Rhinos’ success came in 1984, when they won almost 100,000 votes and came in fourth place, though they won no seats. (However, their 0.79% of the popular vote might have given them two seats under some electoral systems.)

The Rhinos disbanded in 1993 after new election rules would have forced them to run at least 50 candidates to be an official party, which they could not afford. Various independent candidates have run under the party banner until the law was reversed in 2004 and it succeeded in becoming a registered party again. Other parties have followed their example over the years, and the Rhinoceros Party undoubtedly remains a cherished part of Canada’s political history.

Finally, let’s turn to arguably the most important and influential “fringe party” of recent years, the Canadian Green Party. The Green Party was founded in 1983 in Ottawa, and ran 60 candidates in the 1984 election and received 27,000 votes (or about 0.2%). A decentralized power structure led to chaotic leadership races and uncertain campaigns throughout the 1980s. The party’s powerful British Columbia bloc often held sway over the party, though its fortunes in various provinces rose and fell (though it was never electorally successful). Joan Russow was the first bilingual leader of the Greens, as well as the first to hold a truly national campaign in the 1997 election. Her replacement, Jim Harris, urged the Greens to act more like a traditional political party and eschew some of its more radical positions. The 2004 election saw Green candidates in every one of Canada’s 308 ridings and receive 4.3% of the vote.

Green Party leader Elizabeth May, via Wikipedia.

In August 2006, Elizabeth May was elected as leader of the Green Party. Her first foray as a Green candidate in the 2006 election saw her personally win 26% of the vote in London-Centre, the best ever results for a Green Party candidate. In 2011, May became the first elected Green Party Member of Parliament for the riding of Saanich-Gulf Islands in 2011, though other MPs had crossed the floor to the party.

Like other parties from the periphery, the Greens reflected dissatisfaction with how the government was responding to the growing Canadian environmental movement and concerns about potentially disastrous environmental consequences of inaction. Globally, Green Parties have achieved far more success (such as the German Green Party), though under May’s leadership, they have had increasing success here in Canada.

The common denominator among each of these fringe parties (barring the national Rhinoceros movement) is regional support (if they won any seats), which was a result of frustration with mainstream parties or Ottawa. Luckily for Canadians, our parliamentary democracy allows regional voices to be expressed if they are strongly represented within specific ridings. Some have successfully become mainstream, such as the Reform Party or the Bloc Quebecois (and arguably the Greens), though often only after many years of electoral failures and growing discontent. Others have remained on the fringe, seemingly achieving little of consequence on the national stage. While we have forgotten many of these parties, they have been and continue to be a crucial expression for thousands of Canadians in our democratic process.