Considering Important Moments in Canadian Political History

/by Matthew Wiseman

Writing an article on significant events in Canadian history is a difficult task for the historian. Although we are supposed to be well-read in topics such as Confederation, Vimy Ridge, universal healthcare, and the 1972 Summit Series, we are taught to apply a critical eye to events and peoples that “represent” what it “means” to be Canadian. The significance of major events should not be overlooked, but historians are cautious to accept “traditional” or “popular” histories that focus too narrowly on select episodes. Certainly, there is much more to Canada’s past than is portrayed in short, made-for-TV Heritage Minutes, to cite just one well-known example. But perhaps professional history in Canada is itself too harsh on many of the topics and themes that seem to resonate with so many people outside the discipline. With this in mind, today’s post takes a brief look at some key moments in Canadian political history that have come to symbolize a nation and its populace.

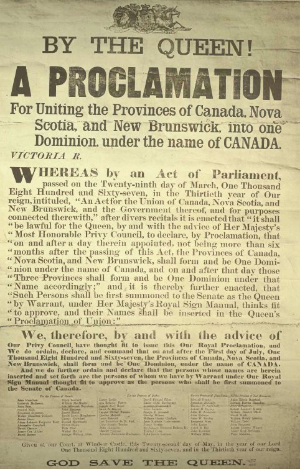

If Canadian history is pegged as a boring subject, much of the pessimistic fodder derives from Confederation. Whereas the United States of America was born from a revolutionary war, the Dominion of Canada emerged because of a political agreement. Which event better lends itself to popular dissemination is obvious. Countless books and films have been devoted to the fight for independence that occurred down south; the same cannot be said of the Canadian case. Regardless, from Confederation emerged the federal Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. The provinces of Ontario and Quebec were formed as a result, and were both united with New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The deal strengthened ties with the British Empire and created the workings of a centralized government, which the likes of John Macdonald and George Brown hoped would be capable of preventing political encroachment from the United States.

Confederation did just that. Using a model of governance based on British structure, Macdonald worked with his contemporaries to establish policies designed to protect Canadian interests at a time when land was “available” for the taking. Macdonald’s vision certainly came with negative implications for many Indigenous peoples, a legacy which still haunts Canada today. But Confederation also forged the makings of a sovereign nation.

Canada’s early political history deserves recognition on certain fronts but gender equality was not top-of-mind in the founding years of the country. The political leaders that came together to agree on Confederation were men who were primarily concerned with gaining lands, resources, and preventing or winning potential wars. The situation did not change much until 1925, when property-owning women finally gained the right to cast a ballot. Understandably, many women who did not own property fought to eliminate discrimination in voting. Yet Canada did not officially adopt new legislation in this regard until 1951 and only because thousands of women fought for suffrage.

Although Egypt gained independence in 1922, the British maintained a military presence in the country until 1952. In that year, General Muhammad Naguib and Lieutenant Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser led a military coup that overturned the Egyptian monarchy. Shortly after the coup, Nasser became President and put Naguib under house arrest. Under the leadership of Nasser, the Egyptians protested the ownership and management of the Suez Canal, an artificial waterway that joined Egypt with the Mediterranean and Read Seas. At the time, the canal was owned and operated by the Suez Canal Company. Both the British and French had stake in the company, which had operated in the cancel since the mid-1800s. The new nationalist Egyptian government under Nasser seized control of the canal, but with the help of Israel, the British and French used military force to reclaim control. The Soviet Union supported Egypt so the United States refrain from action.

As the situation escalated, Lester Pearson worked with the United Nations General Secretary Dag Hammarskjöld to draft a resolution that called for an immediate ceasefire in the region of the canal. The UN passed the resolution and created the United Nations Emergency Force to facilitate the ceasefire and restore stability. For his efforts, Pearson was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957. Canada immediately gained an international reputation as a “peacekeeping” nation—a reputation that has since become closely associated identity in amongst many Canadians.

Cancellation of the Avro Arrow, 1959

The Canadian CF-105 Avro Arrow was an all-weather, supersonic missile-armed jet interceptor. Designed as a large delta winged aerodynamic aircraft, the Arrow stood 14 feet high, 77 feet long, and at its widest, it was 50 feet. With precision design to reduce drag at high altitudes and a powerful twin-engine system, the Arrow thrust past its competition and become a benchmark in aeronautics design and technology. Due to cost overruns in engine design, the Arrow never achieved its maximum potential. Nonetheless, the aircraft still managed to achieve revolutionary speeds that exceeded Mach 2, which is more than twice the speed of sound. This was important at a time when the Arrow was designed to intercept long-range nuclear-carrying Soviet bombers.

The Arrow meant air defence to Canada in the midst of an escalating Cold War, but its program grew costly and the government of John Diefenbaker decided to cancel its production on 20 February 1959. The day has since been known to Canadian history as “Black Friday.” Shortly thereafter A.V. Roe (the maker of the Arrow) folded and thousands of Canadians lost jobs at the main plant as well as subsidiary divisions nation-wide.

In theory, jet interceptors were becoming obsolete, or so Diefenbaker’s government decided. But for nearly a decade the Arrow was pitched to Canadians as a national symbol and its cancellation marked a major shift for the country. Canada immediately began a downward spiral on the international aeronautics stage, and the nation entered a recession. Diefenbaker’s popularity amongst the public took a hit and his government was defeated at the polls within three years. Historians continue to debate the implications of the Arrow on the Canadian economy and the outcome of Diefenbaker’s political career, but the symbol of the Arrow (mythic or real) continues to persist.

The maple leaf is today an enduring symbol of Canada, but for over six months in 1963 and 1964 Canadians debated their national flag. On June 15, 1964, Prime Minister Lester Pearson proposed his plans for a new flag in the House of Commons. The debate lasted more than six months, day and night, in the longest filibuster in Canadian history.

Many politicians were sickened by the thought of a Canadian flag that did pay respect to Canada’s colonial ties to Britain. Surely, many thought, if the new flag is to without the “Union Jack” than it must still represent the colour blue. Others in both public and political circles disagreed, and called for a complete symbolic separation from Britain. The debate over the proposed new Canadian flag ended on December 15, 1964. The “Maple Leaf flag” was adopted as the Canada’s national flag, and its inauguration took place within a few months on February 15, 1965. Since 1996, February 15 has been commemorated as Flag Day.

The 1960s was an active decade in Canadian politics that saw the introduction of universal healthcare and a new national flag—both changes were hotly contested within and without political circles across the country. The debate over medicare began with Saskatchewan Premier Tommy Douglas, who believed that each province should provide their residents a basic level of care. Douglass faced strong pressure from doctors in his own province, many of who showed great concern over the thought of being under government control. Concern turned into protest when a group of doctors decided to strike. The strike lasted for 23 days until protestors caved. Afterwards, Douglas went on to lead the newly formed NDP and within 10 years, the remaining provinces in Canada adopted the same model of healthcare.

The Canada Health Act became official two decades later in 1984, but by then Canadians had experienced first-hand the immediate benefits of provincially funded health systems. Medicare it works today is highly costly and receives heated criticism for inefficiency, but today there would most likely be a revolution if the government attempted to recede the provincial benefits that Canadians receive. For his efforts, Tommy Douglas received high praise from his contemporaries and has since been voted “The Greatest Canadian” by a poll conducted by the CBC.