Let's Clean House: Early Negative Political Advertising in Canada

/Part 5 of our Canadian election Political History Series. Check out last week's history of the NDP!

For those of us who follow politics closely, the cynicism and shallowness of the modern campaign advertisement strikes us as crass, boorish, and worst of all, boring. A sinister voice intoning dire warnings about a party's opponents, an upbeat song and saccharine delivery of platitudes soothing you into complacency: at this point, we are all well acquainted with the tricks of the trade. The relentless application of the art of advertising, however, is a fairly recent development in the world of Canadian politics.

Susan Delacourt argues in Shopping For Votes: How Politicians Choose Us and We Choose Them (an essential read for those interested in the history of advertising in Canadian politics) that the first truly modern use of advertising in a political campaign was the 1952 New Brunswick provincial election. There, an enterprising young advertising executive named Dalton Camp was recruited as advertiser-in-chief of Hugh John Flemming's Progressive Conservative campaign against the well-entrenched incumbent Liberal Premier J.B. McNair. McNair, ironically, had been the first politician to hire an advertising agency to direct his campaign in 1944.

In this post, we'll explore some of the newspaper ads of this pivotal election. All the ads used in this post appeared in the Sackville Tribune-Post, whose archives can be consulted in the microfilm room at the Mount Allison University's Ralph Pickard Bell Library in Sackville, N.B.

Before Dalton Camp's makeover of the traditional political campaign, advertisements in newspapers were dense, wordy, and typically focused on self-promotion rather than attacking. Take, for example, this Liberal ad:

Don't worry if you can't read every word on it. It's essentially a distillation of the 1952 Liberal platform, each plank accompanied by a substantial explanation. This was typical of McNair's ad team. It is also unfocused, which is contrary to one of the first rules of advertising. In trying to sell McNair with a grab-bag of past achievements and promises for the future, it quickly loses the attention of the reader. Another Liberal ad managed to be even denser:

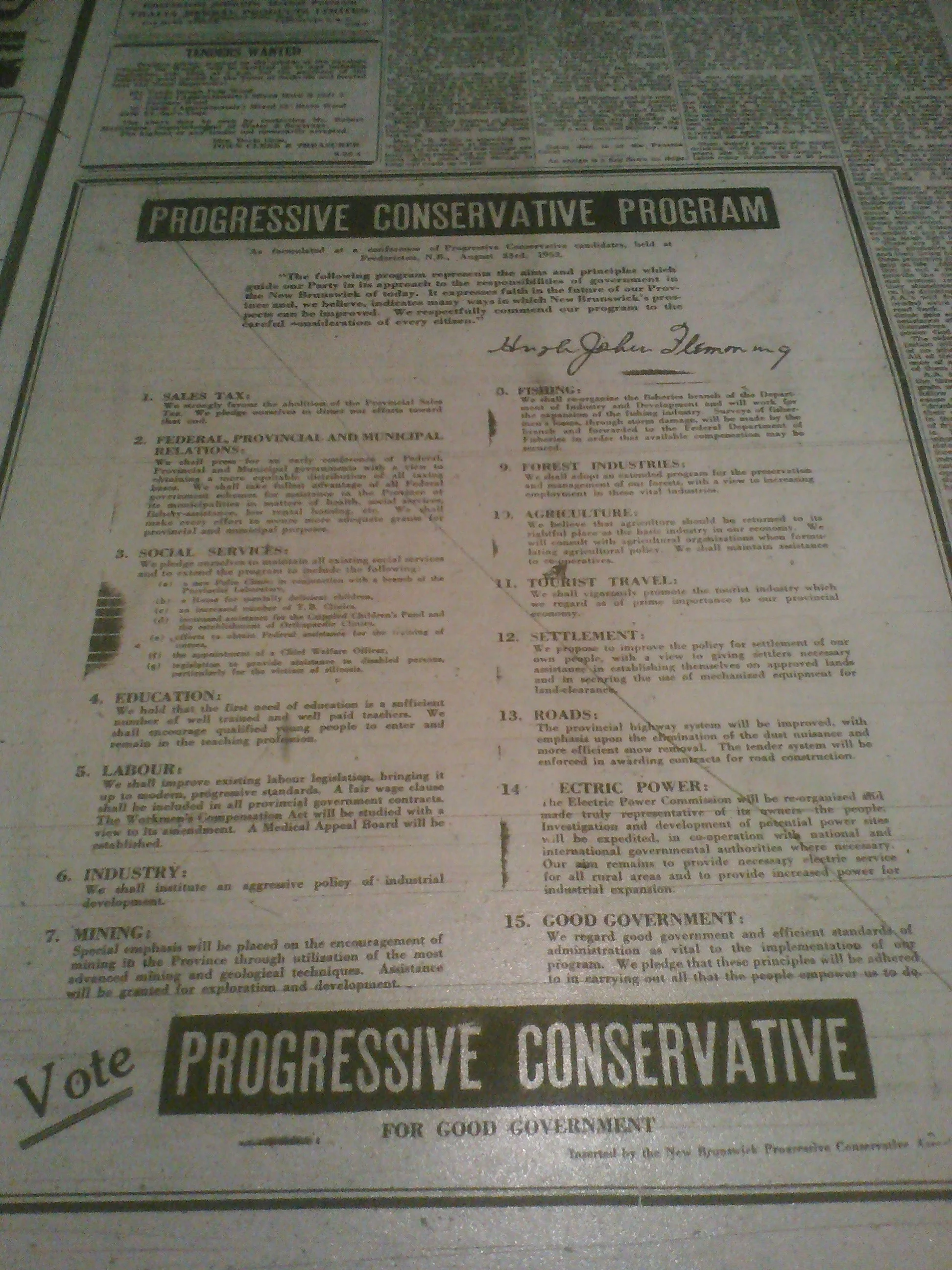

This ad focuses on the achievements of the Liberal administration since 1935. Like the broad list of promises in the previous advertisement, it fails to frame a 'ballot question' for 1953 beyond 'John McNair,' whose name appears prominently on most Liberal ads (though not this one). Early Progressive Conservative ads went along with this sort of staid, sober campaigning:

Like the Liberal advertisements, this P.C. ad trumpets aspects of the platform in some detail (though the increased readability demonstrates that they aspired to pithiness in a way that the Liberals didn't). Flemming, the P.C. leader, is hardly mentioned. Instead, opposition to the sales tax recently imposed by the Liberals topped the list of Tory promises. Camp, however, was still unhappy with this approach. In a speech at Carleton Universityin 1996, Camp reminisced about the state of campaign advertising in the mid-40s: “In the general election of 1945 with John Bracken as the Party’s leader, the Conservatives published a full page newspaper advertisement, in which it reproduced the party’s entire election manifesto - a jungle of words in small print. So repellent to the eye as to drive the reader to the editorial page.” This P.C. ad was not much of an improvement.

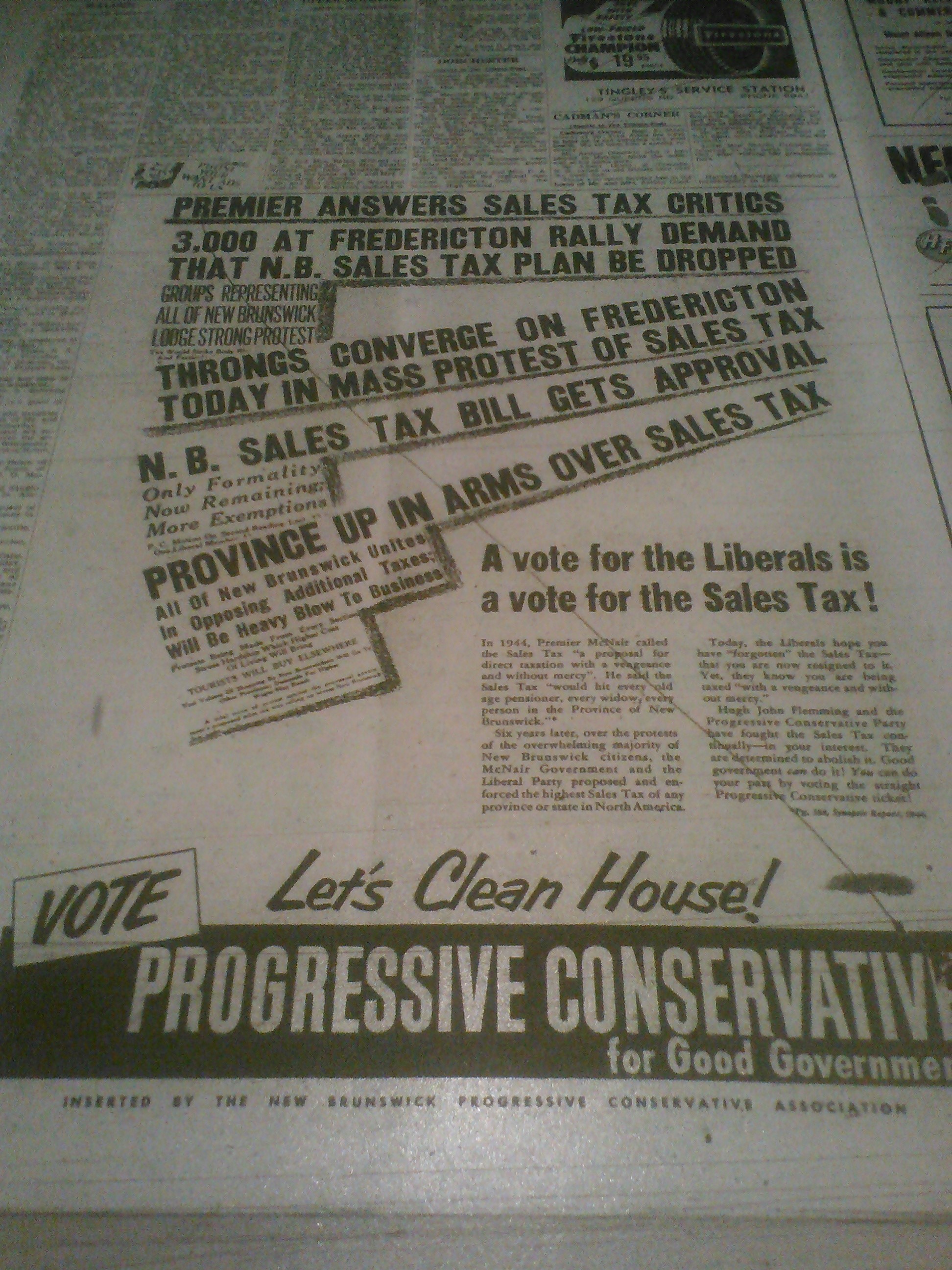

The next ad, however, refined this approach. It was a direct attack on the Liberal sales tax. The Tories had found one of their 'ballot questions.'

This advertisement is much more visually striking than its predecessors, employing a mix of fonts, text sizes, and even incorporating graphics and a catchy slogan (“Let's Clean House!”), which became a mainstay of the Camp camp in 1953. The ad wizard himself went so far as to pen P.C. 'advertorials' in major newspapers under the name “L.C. House!”

This escalation prompted a response from McNair's team, who stayed positive but embraced a more vibrant style of advertisement that doubled down on promoting the Premier as the Liberals' greatest asset.

This ad targets accomplishments in a single policy area instead of continuing the scattershot approach that the Liberals had used earlier in the campaign. In the 1950s, New Brunswick and other provinces were beginning to transition to a larger role in the administration and provision of health care to their citizens. In addition to the specificity of the ad, we can also notice the obvious changes in design: small cartoons illustrate the different facets of the Liberal health policy (also helpful in a province with high rates of illiteracy!). The Tories disagreed, however, that the Liberals had been good for the province's health:

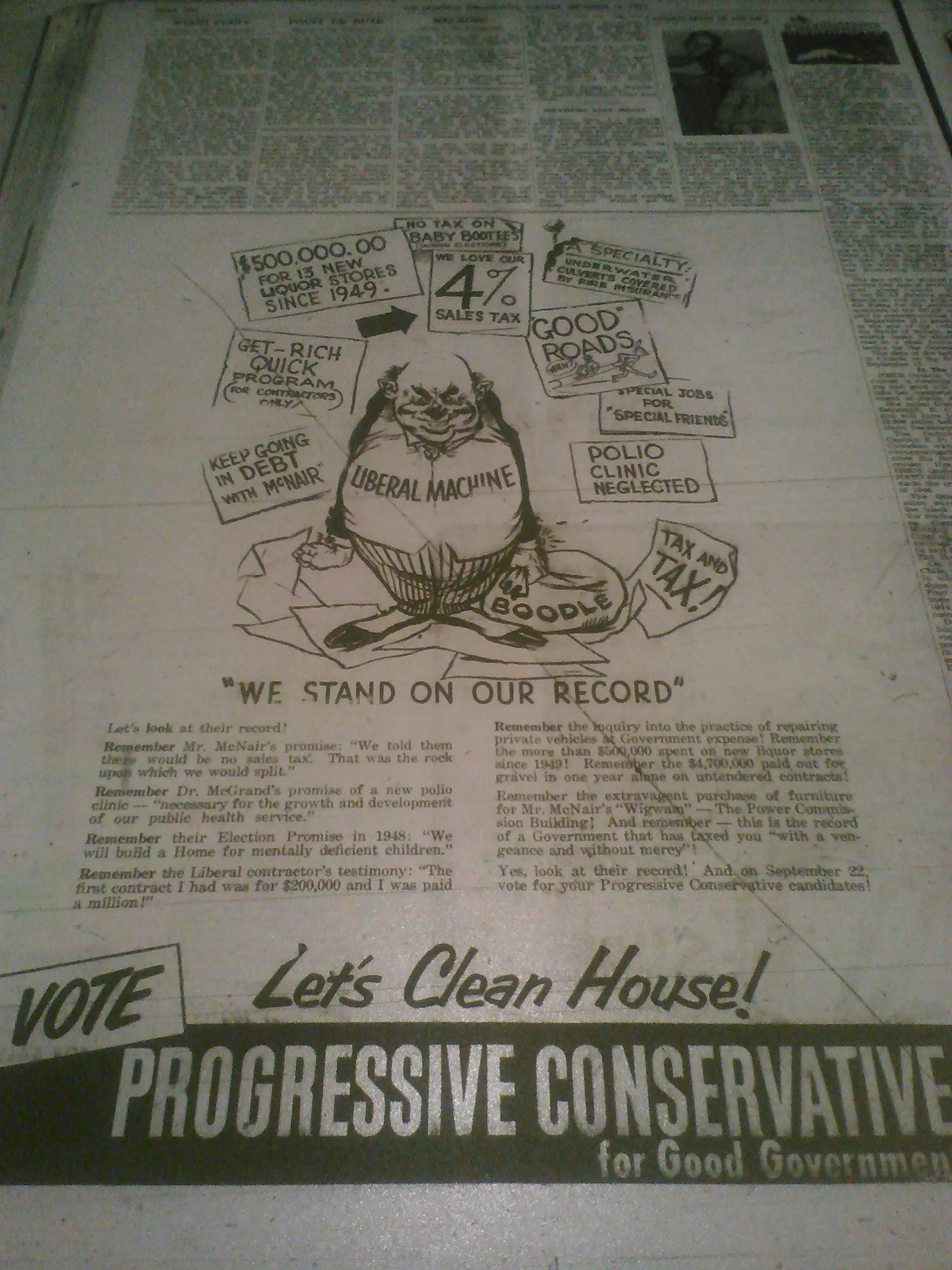

This ad is exceptional. Its hostility, sheer nastiness, and outright accusations of criminality are unsurpassed by attack ads even today. In it, doctors administer a bitter medicine to the 'New Brunswick Taxpayer', the 4% sales tax (with a threat/promise to increase to 6%, and keeping other 'remedies' on standby). Mr. 'Lib machine' prepares for the patient's death with a tasteful wreath, while standing on a bag of ill-gotten loot for his friends. This was only one appearance of 'Mr. Liberal Machine' and his bag of 'Boodle.'

Once again, this Tory ad deploys the 'Let's Clean House!' slogan, and concentrates on attacking the Liberal record in lurid terms rather than promoting the Conservative platform. 'Mr. Liberal Machine' is also back, sneering with pride (?) about the government's record, which involves (according to the acid pens of Tory copywriters) graft, debt, taxation and neglect of key services.

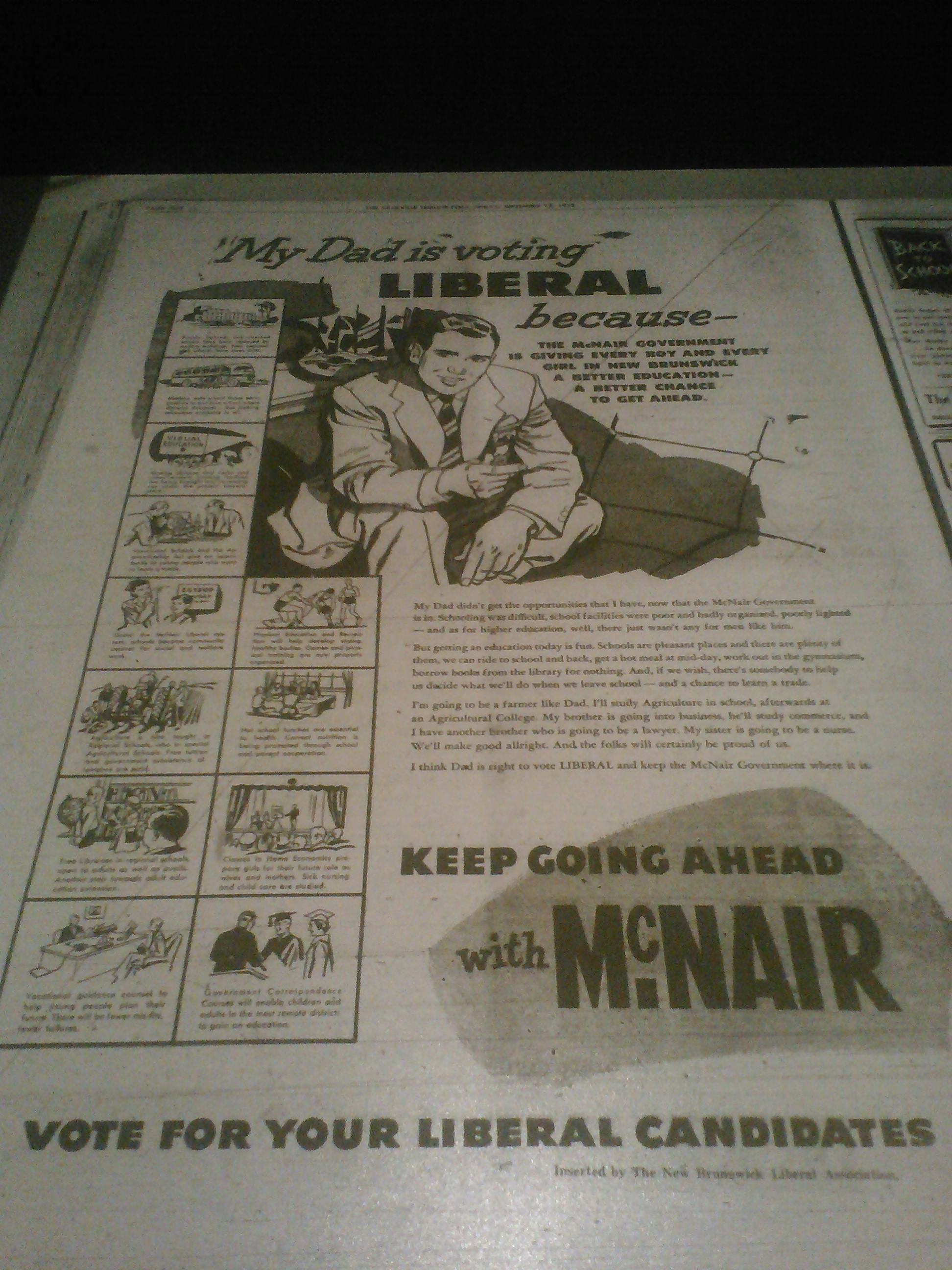

The McNair team, to their credit, never stooped to this level, and continued to run blandly inoffensive ads touting the Liberal record in key policy areas. Here was their take on education, for example:

Once again, smiling cartoon people celebrate the years of Liberal prosperity. A short letter from an (almost certainly fictional) schoolchild extols the wondrous opportunities afforded to his generation by Liberal munificence and implores his father (and readers) to stay the course.

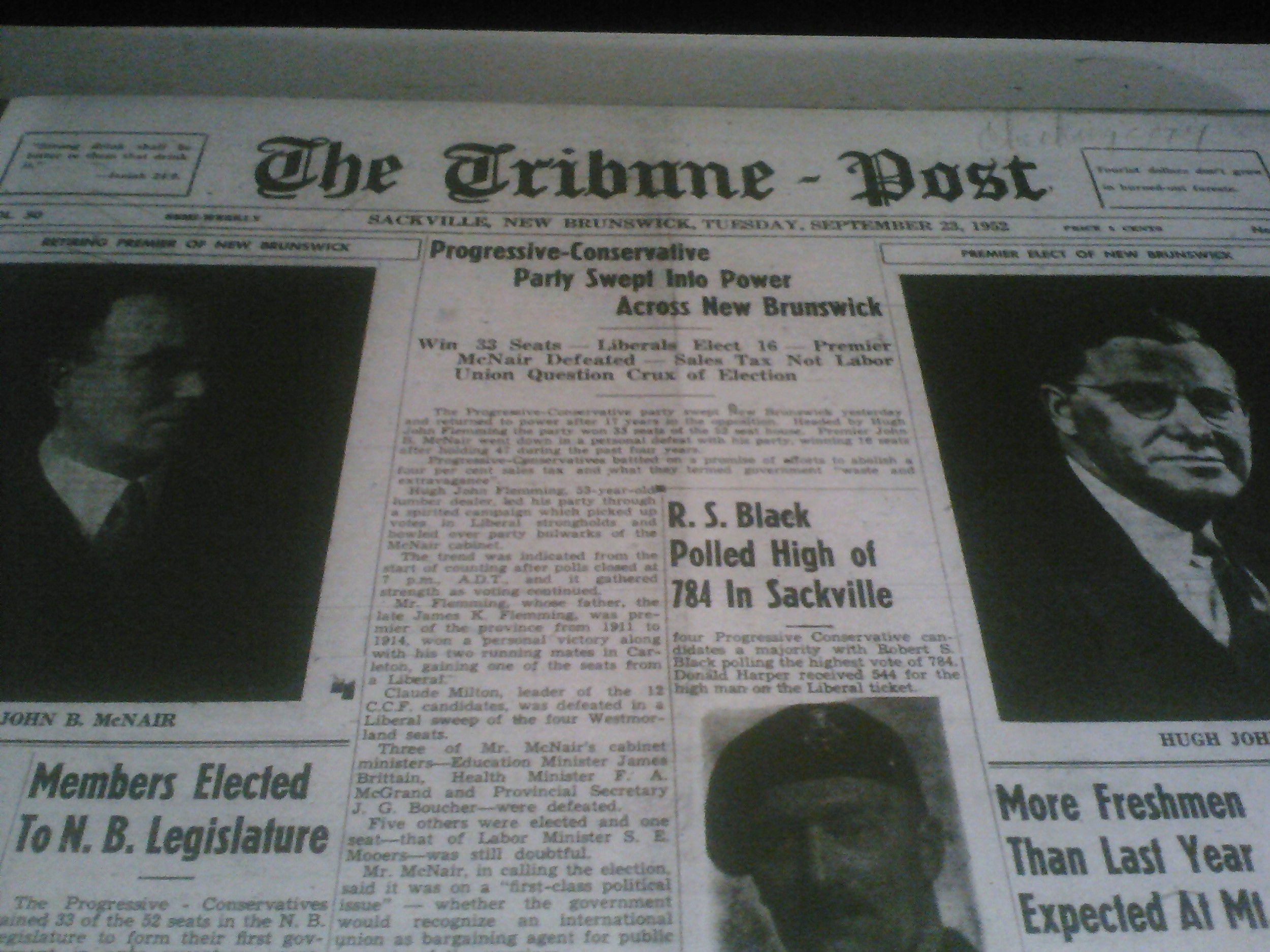

What was the result of these two methods of campaigning? The McNair government went into the election period with strong public support, while Flemming's Tories lagged considerably. And yet, on election day...

The Tories managed to sweep into power with a thumping majority. And as they subheadings of the Tribune-Post's front page indicate, the Tories had managed to turn the election into a referendum on the unpopular sales tax (which they did not, in the end, repeal).

The short, highly visual and hostile style of advertisement introduced in this election was not immediately adopted at the federal level. Louis St-Laurent's Liberals ran ads in 1957 that looked just like McNair's. The federal Liberals, however, were much cleverer with regional and demographic targeting than the McNair team had been.

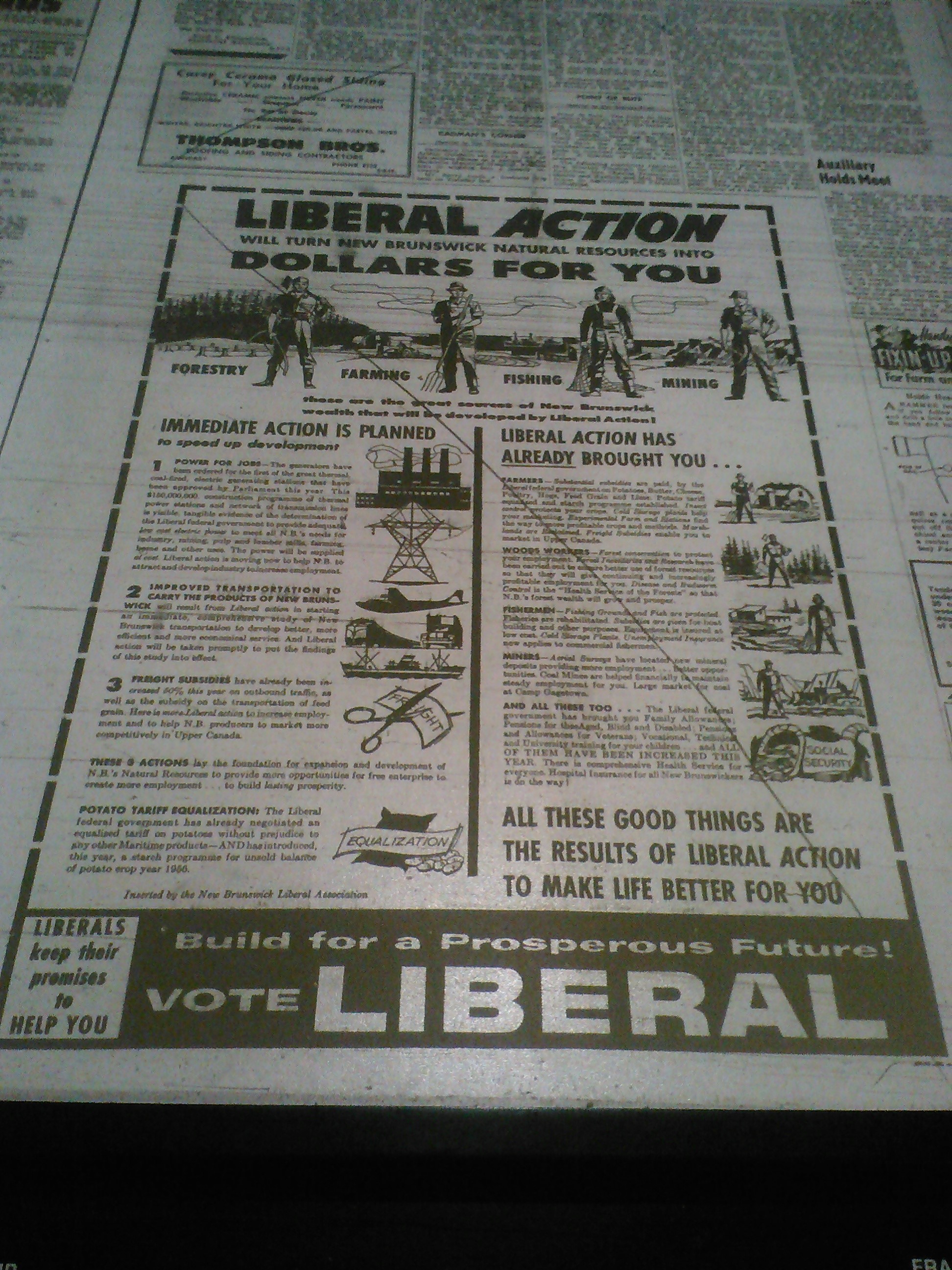

Once again, the Liberals were running on their record and trumpeting their achievements. This ad in particular is pitched to voters in New Brunswick, suggesting that the Liberal campaign team were producing local versions around Canada. Similarly, the Liberals ran advertisements playing up their appeal to both women and young people.

Interestingly, the provincial party paid for this particular ad. In the Maritimes, the provincial Liberal parties are directly tied to the Liberal Party of Canada, and share expertise and personnel. The ad is strikingly similar to the McNair ads of the 1952 campaign: small cartoons illustrating policy promises and achievements, watched over by a smiling face. The direct appeal to women in this ad is accompanied by 'family-friendly' policies like education, welfare, health and family allowance; an interesting early venture into what Delacourt calls “microtargetting” of specific demographic constituencies.

This particular advertisement is also “microtargetted,” this time at young voters, and emphasizes casting an effective vote (note especially point 2 in the ad, which somewhat obliquely implores the young not to vote for the CCF).

Election advertisement, like elections themselves, can be a sordid business. What are the lessons we can draw from the use of advertisements in the 1950s? I would argue that the New Brunswick election, and the federal elections of the late 50s, proved a turning point in the history of Canadian political advertising. Attack advertisements, by no means a new phenomenon, reached a level of distribution and technical sophistication heretofore unseen, and advertising in general became much more precisely targeted to specific demographic sub-groups (like young voters and women in the examples above, but every niche under the sun in due time!). These tactics have endured to the present day (unfortunately), and microtargetting has spread to policymaking, as well.

The modern Conservative Party's aggressive use of attack advertisements outside of the formal campaign period helped sink Liberal leaders Stéphane Dion in 2008 and Michael Ignatieff in 2011, ensuring the first majority Conservative government in two decades. Attack ads can sometimes backfire, however: Paul Martin's Liberals were widely mocked for insinuating that then-Opposition Leader Stephen Harper had a nefarious “hidden agenda,” and especially for a bizarre ad that claimed that under a Harper government, there would be troops in Canadian cities. The Progressive Conservatives' “face ad” of the early 1990s that mocked Liberal leader Jean Chrétien, who had suffered from Bell's palsy as a child and consequently had minor facial paralysis, was widely decried as a low blow.

As for microtargetting, its nefarious influence has spread beyond simple advertising: it has merged with policymaking. In its first mandate, Stephen Harper's Conservative government lowered the Goods and Services Tax, despite a chorus of opposition from academic economists. Prime Minister Harper's sometime chief of staff, Ian Brodie, later said, “Despite economic evidence to the contrary, in my view the GST cut worked ... It worked in the sense that by the end of the ’05—’ 06 campaign, voters identified the Conservative party as the party of lower taxes. It worked in the sense that it helped us to win” (see Joseph Heath's Enlightenment 2.0 for a fuller treatment of this phenomenon). The creation of myriad 'boutique' tax credits, ranging from credits on children's sporting equipment to acupuncture, further served as fodder for a system wherein questions of governance and marketing become dangerously intermixed.

This is not to suggest that the Tories are the only guilty party in this marriage between the work of political marketing and government. The three major federal parties in this year’s election are all attempting to campaign through the 'boodle bag', with hefty promises to families and the always-nebulous 'middle class,' as well as giveaways to select groups likely to support a given party. Today's voters are the inheritors of a system in which increasing technical sophistication in market research and advertising have robbed democratic politics of some of its non-partisan dignity. Remember that that this did not come from nowhere, and there is nothing foreordained about the state of political advertising. The public is within its rights to demand and vote for better.

In Part 6 of our series, we look at fringe parties and their impact on Canadian politics.