2015 Election Primer: Politicians and the Media

/Over the past week, Prime Minister Stephen Harper met with Governor General David Johnston and received approval to dissolve the Government, kicking off what will be the second longest election campaign in Canadian history. Although each party leader outlined their party’s priorities individually, for many the official campaign began last night with the first election debate. The leaders squared off and today news outlets are filled with detailed coverage and analysis of the event. Rather than analyze the debate or the performance of each party leader, in today’s post we take a brief look at the history of relations between politicians and the media.

Those familiar with the game of rugby will associate a scrum or scrummage with the recognizable image of players gathered tightly around the ball, jockeying for position with their heads down and trying to restart the play by breaking away or kicking the ball out of a densely packed circle of players. The rugby scrum can certainly be rough, brutal and at times painful. Those unfamiliar with the game might well recognize the rugby scrum, but may also associate the term with media. To followers of sports and politics, a scrum is also the term used to describe a barrage of questions from various media personnel. In Canadian politics, usually on Parliament Hill, reporters can often been seen surrounding available politicians with microphones, cameras, lights, notebooks, and pressing questions that demand quick and insightful answers. Although markedly different from the rugby scrum, this too can be a rough and painstaking event for those involved. Despite how it may look on TV, neither side particularly enjoys the scrum as a form of communication. Politicians often feel cornered and shy away from questions, while the media feel rushed to ask questions that might produce a useful soundbite but seemingly empty answer. Even still, the scrum has become an enduring tradition in Ottawa.

The modern scrum began when television news media began to cover politics in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The term “scrum” was first associated with the hallways of Parliament during the early years of the Trudeau government. As Prime Minister Trudeau often spoke in a quiet voice, reporters learned to get answers by encircling him and jockeying for question time. But scrum-like atmospheres have been around much longer. Dating back to the premiership of Sir John A. Macdonald, records describe how and when the earliest parliamentary press gallery gathered outside the prime minister’s office, waiting with pen in hand to record a useable quote for the next edition.

The scrum represents competition, and tests both intelligence and will. Is has the ability to work to the advantage of either side and has claimed its share of victims. Journalists often claim that the politicians have the advantage. Depending on availability of the politician, reporters may jockey for position and still not get the chance to ask a question. Likewise, politicians often claim that it is the members of the media who control and benefit from the scrum. When rushed to answer, politicians have been known to perform poorly depending on question and circumstance. While both sides have legitimate arguments, the scrum seems sure to stay.

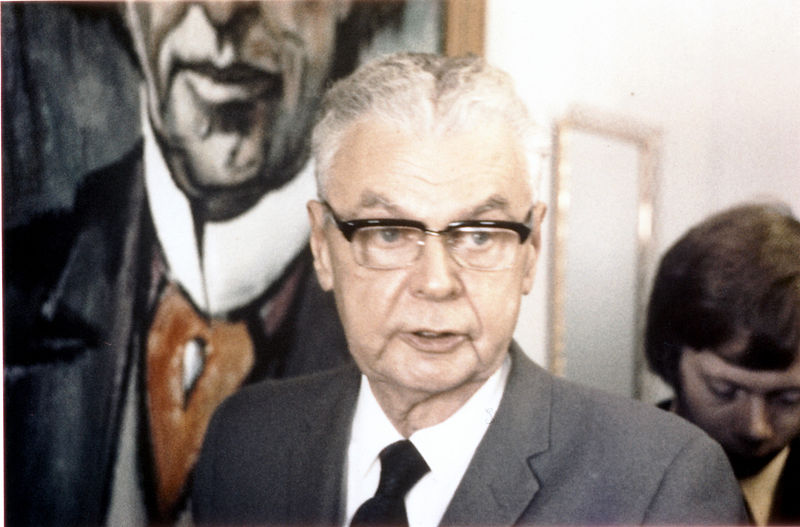

Historian Allan Levine has noted that Canadian journalists showed much more respect for politicians prior to the 1930s. Partisanship was a staple in the parliamentary press gallery for decades. Consider that, in 1957 when John Diefenbaker’s government took power, the Tory prime minister knew exactly which Conservative reporters and Conservative newspapers he could trust. The relationship between Diefenbaker and the press was set early. Known as a strident populist, Diefenbaker was the first to officially acknowledge and invite media personnel into the corridors of Parliament Hill. The relationship hurt him in the end, as various media outlets that had supported his premiership shifted loyalties and ran stories that ultimately damaged his public image.

In light of the oft rocky relationship between prime minister and media, Liberal leader Lester Pearson still classified newspapers he received as “Liberal,” “Conservative,” or “Independent” when he took over the leadership in Canadian Government in 1963. This does not mean that all journalists supported a particular party affiliation, but complete objectivity, then as now, was certainly not a prime fixture of Canadian news media. The introduction of TV added another complex dimension. Because on-screen news emphasized confrontation and dramatic moments, TV reporters began in the mid-1960s to “push buttons” in hopes of securing juicy answers. The introduction of political analysis also changed the landscape. Reporters had always analyzed politicians in print, but TV news had the ability to reach a wider and more diverse audience. Newspaper and TV journalists began to take on the role as the “unofficial opposition,” intent on covering politics but also exposing corruption in government. By so doing, the news media began to take on the role of public protectorate. Stories such as John Turner’s alleged drinking problem and Brian Mulroney’s Gucci shoes, did more to damage personal images than cover important political events.

As the 2015 campaign begins, perhaps the most important lesson from this brief sketch of relations is patience. Not all news media are bad, and not all politicians are deceiving. From both sides we are sure to hear positives and negatives; we are sure to witness smack talk against the opposition; and we are sure to hear the media speculate as to whom best will serve as the next leader in Canadian government. Don’t believe all you hear, don’t believe all you see, and don’t believe all you read. A critical citizenry breeds strong democracy.