We're The Ones That Did It? Canada and the Burning of Washington

/For Canadians, a popular retort about the War of 1812 is our supposed role in the burning of the White House. In 1814, British soldiers landed in Washington and looted the American capital. Canadians, in their minor role in the conflict as auxiliary forces, sometimes say that Canadians themselves burned down the White House. Despite any claims you might hear, it was British soldiers behind one of the most notable moments of the war. Where and how did the myth of Canadian involvement appear?

The War of 1812 began – as you might have guessed – in 1812. As Europe was embroiled in the dying gasps of the Napoleonic Wars, the United States under President James Madison decided it was an opportune time to redress American grievances with Great Britain that had been growing for decades. Tension on the western American frontier (then beginning in Ohio and Illinois), the impressment of American sailors into the British Navy, and British trade restrictions all contributed to the eventual declaration of war by the United States in June of 1812.

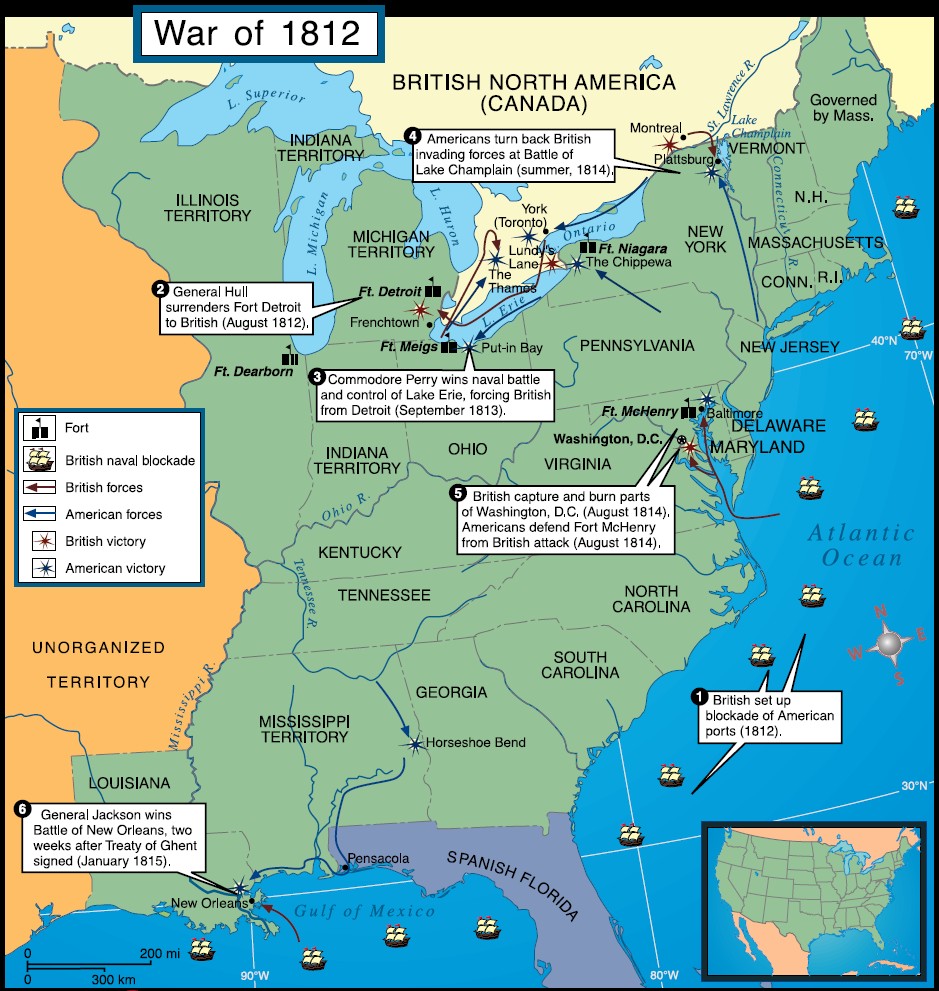

A map of War of 1812 offensives, via jb-hdmp.org.

After a series of successes by British and Canadian forces in the Great Lakes regions in 1812, the Americans eventually pushed back in 1813, slowly encroaching up the Ontarian peninsula and securing naval control of the Great Lakes. By 1814, the war had entered into a stalemate as Americans could not force a British defeat, nor could the British cause serious harm to their American foes. The first defeats of French Emperor Napoleon in late 1813 and early 1814 allowed the British to reallocate their forces to the North American theatre that had been a secondary concern since the war’s beginning.

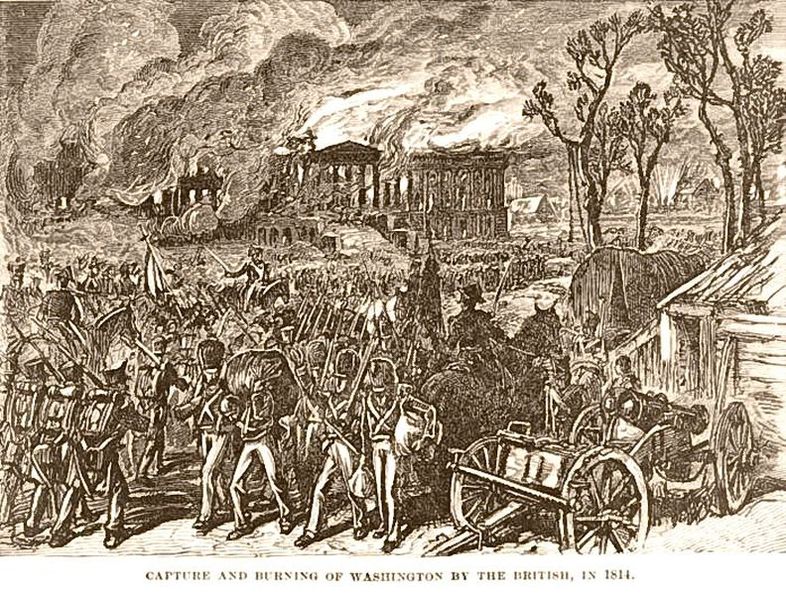

"Capture and burning of Washington by the British, in 1814," via Wikipedia.

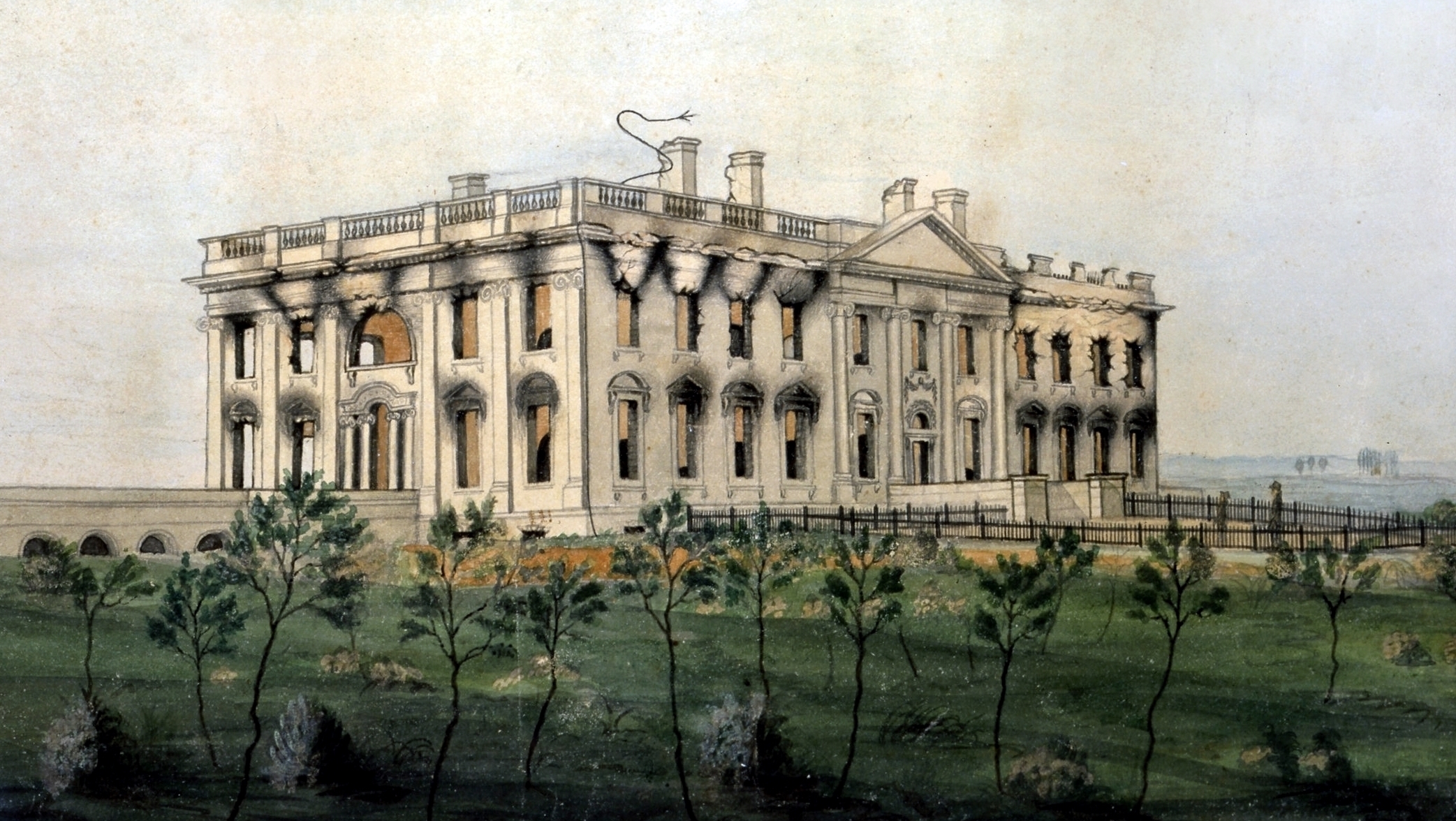

A new series of offenses were planned, launching attacks into the United States from Quebec into the northeastern states, a naval attack against Washington, and an attack from the Gulf of Mexico at New Orleans. Of these offensives, the attack against Washington was the most successful. On 3 August 1814, a force of British soldiers landed in Chesapeake Bay and advanced quickly onto Washington with 4,000 Redcoats. American militia were no match for the British veterans of European battles, and President Madison and the Cabinet soon fled the city. In revenge for the American burning of York (now Toronto) in 1813, they burned many of the public buildings, including the Presidential Mansion. The Mansion was later repainted and became popularly known as the White House. The British considered attacking the better-defended city of Baltimore next, but after the death of the British General Robert Ross (and a tornado!), they returned to their ships and retreated to Jamaica. They considered the burning and looting a success – they certainly fared better than the other British offensives of 1814, such as Canadian Governor General George Prévost’s defeat at the Battle of Plattsburgh or the defeat at New Orleans (which technically occurred after the war had ended).

By 1815, the Treaty of Ghent ended the war and essentially returned the status quo for the British and Americans. The Aboriginals who occupied much of the western frontier, despite successfully fighting for the British, lost their defacto protection from American encroachment and quickly fell victim to American expansion. While no one “won” the war, the Aboriginals certainly lost it. Canadians, who had endured American occupation of Ontario and fought in the British militia, took the war as more proof that their loyalty to Britain was worthwhile.

The War of 1812 eventually took on mythological proportions, particularly for the descendants of the United Empire Loyalists – those British subjects who had settled in Canada after the American Revolutionary War and endured the War of 1812 as well. Many elites, largely centered in Upper Canada (Ontario), mythologized the successful defence of Canada. They first celebrated event such as the victory of Isaac Brock at Queenston Heights and repelling the American invaders as well as Laura Secord’s journey through the forest to warn British commanders of an impending attack. By the end of the 19th century, Canadian imperialists also marked the triumph of Canadian militia during the war.

The Imperialists emphasized their vision of a united Canadian nationality, attached to their British past, where French and English Canadians fought the American menace together. The Canadian history of the War of 1812 highlighted how Canada had shared the burden of imperial defence, which, in the late 19th and early 20th century, was an important political aspect of these myths. Missing is any mention of the supposed Canadian role in burning the White House. It’s clear that for that generation of Canadian Imperialists, the burning of the White House was not significant. The War of 1812 was all about the defence of Canada and the defeat of Americans on Canadian soil by a "united" Canada that included French and English, not about incursions into American territory.

The President's Mansion by George Munger, via Wikipedia.

So where did this myth originate?

We searched through Google Books and Google Scholar looking for references to burning the White House. Admittedly, Google is not a comprehensive search, but it allows for a general look through sources from the 19th and 20th century. We searched for terms like "burned the White House" Canada; "burned by Canadians" "White House"; "burnt by Canadians"; "burnt by the Canadians"; etc. It is interesting to note the difference between searching on Google Books for "Canada burned" "White House", which yields 7 results, compared to Google Search, which has 1160. The Canadian burning of the White House is talked about a lot online, but less so in published books. Unsurprisingly, “British burned” “White House” has many more results. When we narrow these searches to books from the 19th century, we see that are no references to Canadians burning the White House, only the British. Books from the last two decades have more references to “British and Canadian forces” or the incorrect statement that Canadians themselves were involved.

That suggests to us that the Canadian involvement in the Battle of Washington is a modern myth, not associated with the United Empire Loyalists, late 19th century Canadian imperialists, or the militia myth. It also seems to suggest that it has propagated online, as there are a lot of questions about whether it’s true.

Still, this preliminary examination is not conclusive. For all we know, it has been passed from teacher to student in Canadian classrooms for decades but never put down on paper by historians and writers because it is wrong. Though this is a tough research question to answer given the disparity and breadth of sources, it seems like it is a claim that has only recently become popular.

Perhaps we might look to another notable addition to the Canadian memory of the War of 1812. In 1991, the Canadian comedy group Three Dead Trolls in a Baggie released the song The War of 1812. Their catchy lyrics tell us that:

And the white house burned burned burned

And we're the ones that did it

It burned burned burned

while the President ran and cried

It burned burned burned

And things were very historical

and the Americans ran and cried like a bunch of little babies

wah wah wah!

In the war of 1812.

Given that the release of this song coincides with the popularization of the myth that Canadians burned down the White House, it must be a source for its spread today. Only in the last quarter century has the myth penetrated popular consciousness of Canadians, and been reepeated ad nauseum online and in private conversation.

If the Canadians burning the White House is a modern myth, it shows us much more about Canada at the end of the 20th century than the one at the start of the 19th. Its popularization in recent years probably tells us much about the Canadian desire to differentiate themselves from the United States, or more likely, the yearning to one-up our powerful southern neighbours. Ironically, Canadians did participate in the seizure of Detroit under General Isaac Brock – the only time an American city in the continental United States has been occupied by foreign forces – which is a far more impressive accomplishment than burning Washington, but one not popularly remembered. At least some Canadians can take solace in that bit of history trivia, where we at least had a role rather than none at all.