Canadian Ad Hoc Defence of the Arctic in the Early 1920s – Guest Post by Trevor Ford

/In August of 2013, Canadians become aware that the Canadian military had been secretly building and testing a stealth snowmobile in the Canadian Arctic. Named Loki, after the mythological shape-shifting Norse god, the snowmobile has been in testing for some time with over $620,000 spent on its development to date. This has led many critics to question what they believe is an exorbitant cost. However, government officials have pointed out that the research was part of a larger plan to increase Canada’s military presence in the Arctic, which includes the placement of ships, troops, and armed bases throughout Canada’s North.

These efforts have largely resulted from the government’s recent increase of focus on Arctic sovereignty. The Arctic has become a more pressing public issue as changing weather patterns shorten winters and open up access to shipping through the Northwest Passage. Experts predict that these changing conditions will lead to industry exploration of the oil and gas pockets that lay throughout the Arctic. These issues make the Arctic a vital economic and territorial issue for the Canadian government. Other nations who share the Arctic also see this possible windfall. Russia, in particular, is a growing concern for the Canadian government. Their publicity stunts, such as planting their flag on the seabed of the North Pole, and their military adventures in Europe have only increased the call for a strong Canadian military presence in the Arctic. For these reasons, the Canadian government argues that the cost of a new stealth snowmobile (among other things) is a necessary expense.

Stealth snowmobiles aside, Canada’s military interest in the Arctic predates the current government’s efforts. Many interesting and far-fetched ideas have been put forward in order to secure Canada’s Arctic territory over the decades. For years the Arctic was perceived as a strategic barrier more formidable than either the vast Pacific or turbulent Atlantic oceans. Yet there was always a notion that the North could be used as an approach into the heartland of North America, and military and civilian officials have always sought ways to maintain at least partial control over Canada’s northern approaches. The first attempts at this date back to the early 1920s.

We can trace Canada’s first explorations of Arctic defence back to a report by the Department of the Interior dated January 1920. In the report many concerns were put forward about American and Danish encroachment into the Canadian North from Alaska and Greenland. The report stipulated that it would be in Canada’s immediate interest to develop her sovereign claim rather than risk an American or Danish takeover. The sub-committee responsible for the report suggested that sovereignty in the borderlands with Alaska could best be maintained by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). After all, the men of the RCMP had already developed a presence in the Yukon during the gold rush years.

The Danish threat originated from Danish controlled Greenland. The sub-committee noted that the Danes were planning several Arctic expeditions into Canada’s North and recommended that the RCMP expand their geographical role by including Mackenzie territory, and the northern fringes of Hudson Bay. Kenneth C. Eyre of King’s College published his PhD thesis on the subject and has noted that, although the department’s report stressed haste in the implementation of its suggestions, the political situation at the time would not allow it. Eyre stated that, “by the time the Report had been fully considered in the Department and the Cabinet, it was mid-1920 and the summer shipping season was too far advanced for Canada to do anything concrete that year.” Due to the changing weather, one idea called for Canada to borrow an airship from the British government. The airship would be loaded with RCMP constables and a season’s worth of supplies and launched from Scotland for a patrol of the north all the way to the pole. If they encountered any Danish or American intruders, the unlucky RCMP officers were to parachute from the blimp and confront the intruding party. Luckily for the constables, this idea was never implemented.

As already noted, the department’s report concluded that the RCMP should represent Canada’s protection in the North when it came to Arctic sovereignty. In fact, the Department of the Interior never even considered consulting with the Department of Militia and Defence over the Northern approaches throughout 1920. Eyre wrote, “there is no evidence whatsoever that anybody—politician, civil servant, professional soldier, or private citizen—at the time considered that the military had or could have a role to play in the establishment and protection of sovereignty.” This was not particularly surprising as the Canadian Militia was greatly reduced in the post-First World War years and what remained was wholly focused on the border with the United States. In the opinion of most professional soldiers, if the United States were to grab Canadian soil, it would be from the South, not Alaska. Thus Canadian soldiers such as the venerable Colonel James (Buster) Brown spent long summers in the early 1920s measuring out the widths of roads along our southern border and other potential crossing points to help plan the defence against a possible American invasion. The Arctic was far from their mind when it came to protecting Canadian sovereignty.

Although the regular army at this time was completely uninterested in the Canadian North, the Military Intelligence Branch (MIB) of the Canadian Militia was not. Semi-detached from the Canadian Militia’s chain of Command, and with an internally focused nature, the MIB developed repeated intelligence notes on possible foreign incursions in the Canadian Arctic and possible counter-attacks. The District Military Intelligence Officer (DMIO) for Military District (MD) 10 became the foremost accumulator of intelligence on the Canadian Arctic. MD 10 included Manitoba, western Ontario (including the area of modern Thunder Bay) and the northern territory of Keewatin (which is now known as Nunavut).

The DMIO for MD 10 in 1920 was Major Gordon Aikins. He believed that the northern boundaries of his district were much more vulnerable than that of the southern border with the US. He thus made many intelligence summaries on the matter in his reports to Ottawa. One of the reports which stands out in the context of present controversy was on the development of an ‘Aero Sleigh’ or ‘Arctic Sleigh.’ This machine, using the construction design of an airplane, was essentially just a sleigh with a propeller. This type of vehicle was not exactly a new concept as a young Igor Sikorsky, of the future industry titan Sikorsky Helicopters, designed a version of the Aero Sleigh that he called an ‘Aerosani’ in 1910.

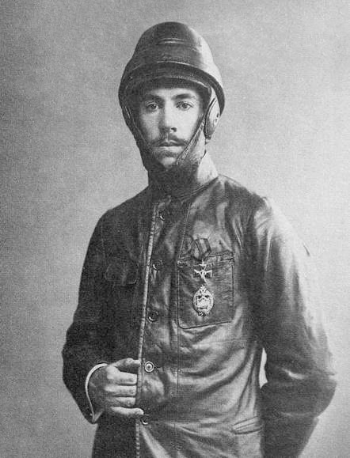

Igor Sikorsky in 1914. Portrait photograph by Karl Bulla.

The Canadian Aero Sleigh design was a separate development from Sikorsky and intrigued Major Aikins so much that he spent significant time promoting its abilities in Ottawa. The sleigh could travel at 70 miles per hour, climb grades of 45 degrees, keep the operator and passengers warm, and most importantly cut travel times drastically. The DMIO believed that the Department of Militia and Defence should purchase hundreds of the contraptions for military purposes in the Arctic. These units could easily outflank any invading unit and ensure Canadian military supremacy in the Arctic. As it turns out, this idea militarily was not too far-fetched, as the Finns would later use dozens of similar machines in their conflict against the Soviet Union in the Winter War. At one point, Major Aikins’ reports were even picked up by the British annual military intelligence reports in 1924, but little came of it. Neither the professional soldiers of the Canadian Militia nor the politicians in Ottawa gave Aikins a second thought. His reports were simply filed and forgotten.

Although intermittent military and civilian action continued throughout the latter part of the 1920s and 1930s, it was not until the outbreak of the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War that any significant actions were carried out. These examples from the 1920s show that there is not much new to the modern techniques explored by government agencies and individuals who try to defend Canada’s North. Nor is it new to see a lack of political or public interest in these endeavors.