Robot Historians and the Future of History

/In a world where technology continues to advance at an incredible pace, each generation is exposed to new and powerful transformations. Facebook, Twitter, and Smartphones were all unimaginable changes to the ordinary person of 1995. By 2035, maybe we will see an unrecognizable world changed by Virtual Reality, Solar Power, and who knows what else. So what might this incredible future hold for history?

Today we are taking a break from history of the past. Instead we are going to do a thought experiment and turn around 180 degrees. We are no longer facing the past, but looking forward to the future. It’s a shrouded road, and we can see almost nothing ahead of us: the future is unknown. If we squint though, we think we can see something. It’s a possible future! Using what we know from looking behind us – which is a much clearer view – maybe we can guess what we see far in distance.

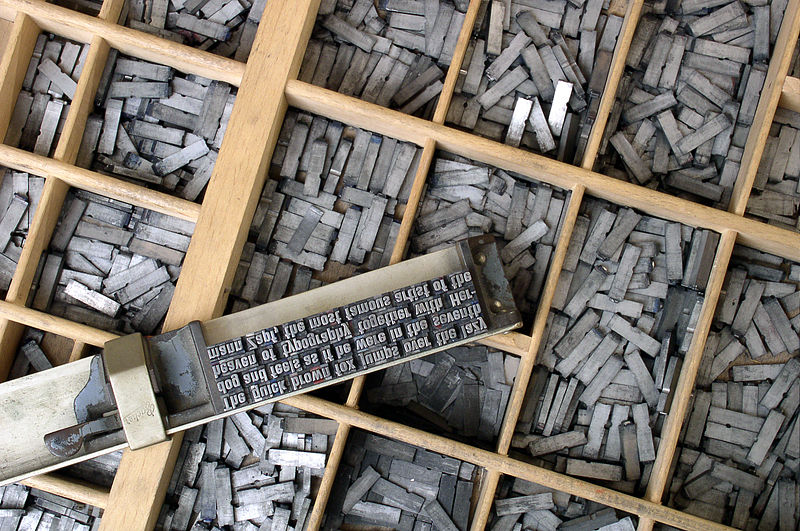

Movable type sorted in a letter case and loaded in a composing stick on top, by William Heidelbach via Wikipedia.

Behind us is the technology that influenced the writing and craft of history. Some societies perfected the oral transfer of knowledge, while others created physical ways to record information. The invention of writing, the printing press, and other technologies that influenced knowledge-transfer are obvious precedents. The better we could preserve and transmit information about the past to the future, the better future historians could understand the past. First, there were stone tablets, then arduously produced manuscript tomes, and eventually the mass production of books. Alongside these inventions, we also created depositories to store pieces of information (libraries) and progress in education allowed more people to read them as well as record their own history. Canada has 99% literacy rate in 2015 – meaning that each Canadian can discover, record, and preserve their own history. Compared to much of human history, this is an extraordinary number of possible historians!

In the last half century, the invention of computers and the ability to connect them via networks has once again revolutionized how we transfer knowledge. The digital age has dramatically increased our ability to record and transmit information. Now we can download every single book in a library to our smartphones, transfer it to our friend in Singapore, and live-stream the whole experience to an audience of millions. No one involved has even left their couch. Knowledge-transfer was once analog (physical) and finite, but is now digital (virtual) and effectively infinite.

Historians have benefited from these advancements. Digital tools allow us to work much faster. We can search archives for sources from our homes, or find the sources online without ever having to leave our desk. Cameras and hard drives can store thousands of pictures of documents from a research trip. Programs can find words in a document for us. Others allow us to write articles faster, communicate them more easily to a publisher or share it with our colleagues. All of these are analog actions that have been improved by digital methods. For the most part, digital has just been a means to do things more efficiently. In effect, every historian is a digital historian compared to a generation ago, even if it’s just using a word processor or email.

There have been hints at what’s possible in the vast realm of the digital. “Big Data” deals with datasets that are so large it is impossible for a human to process them properly. Instead, we use programs to collect this massive amount of information and anlayse it. Think about millions of pages of text that would take a lifetime to read even a fraction of them. Historians like Ian Milligan are pushing the boundaries of Big Data history, and more and more historians (and other scholars) are wondering what history will look outside the analog world. That is, not just how it made analog methods faster, but how technology has created entirely new ways of looking at the past.

So now let’s turn towards the road stretching into the future and imagine what those shrouded, distant vistas might look like.

One stop in the distant future might be a time where we see Robot Readers. As software advances, we will inevitably reach a point where computers cannot only identify words, but read them as humans do. They will understand grammar, syntax, and context as well as look for words on a page and comprehend their placement. They will understand when they see “Document No.” that whatever comes after that is a document number, and put that into a database. When it skips from document number 14,235 to 14,237 it will realize that something is missing. Computers will read documents and tell us what’s in them, and do so at an extraordinarily faster rate. We hope that computers will also be able to read handwritten documents – the scourge of historians and OCR alike – and convert them into easy-to-read printed text. They could translate documents from one language to another flawlessly, further expanding the global connections between historians and their study.

Robot Readers would allow historians to look at the past through the lens of “Big Data” at what we could call “small data.” They might discover missing documents, unusual phrasing, or the prominence of certain topics within a large dataset. Historians would tell a program to search for anything related to say, waffles for breakfast, and the computer would spit out hundreds or thousands of documents from archives around the world that talk about waffles, about breakfast, about nutritional information, and so on. It would be closer to the Computer on Star Trek than Google – it would understand which documents are actually about waffles the food and which are just about waffles the verb, and sort them for you.

The “longue durée” of history will lengthen immensely. Why look at a single decade when you can seamlessly examine trends across centuries. Transnational will no longer be a buzzword, but an unavoidable fact. National borders will be as porous as they are on the internet today. Why only examine the history of sugar in Canada when you can trace its spread across the entire world just as easily? As Twitter and Facebook are archived (after all, who will care about the personal information of someone 100 years dead?), social relationships and cultural connections will be mapped out across our modern-day networks. Private messages might reveal startling information about the lives of yet unknown historical figures.

In this future, methodology would rule. Methodological decisions force historians to emphasize different sources, different time periods, and different questions about the past. Today, methodological loyalties divide historians as they disagree about how to best look at the past. Some argue that accuracy is more important than interpretation. In a world where every source is at your fingertips, deciding which sources to examine and why will be far more essential to the historian’s craft. Methodological differences might be minimized, as there will be so many more ways to categorize and examine this large number of sources, but everyone will have to adopt a clear methodological approach. If we imagine historians as crafters of lens through which we see the past, they currently have to design that lens purposefully to narrow their view. If they had access to any size of lens with any focus, methodology helps point that lens at the right places.

one vision of a Robot Historian, from the Pixar movie WALL-E.

Farther into the future, we see the development of artificial intelligence into the Robot Historian. These machines have access to every document that has ever been preserved in their digital form. At some point in the future, we can imagine that our lives will be documented and preserved on a massive scale. “Archiving” something will be a matter of automation, rather than sending to a physical archives. Nearly everything is now being recorded and preserved for our Robot Historians.

A quarter century ago, Manuel de Landa presented the view of a “Robot Historian,” but focused on what topics a Robot Historian might choose over a human one. Let’s just imagine a world where a computer not only understands the different lenses through which we can view the historical record, but understands where to point it. Human historians have become extinct. A computer will answer any questions we have about the past, to the best of its ability. They will also invent new ways of looking at the past that we have never even considered. Perhaps they will bring about Isaac Asimov’s fictional field of “psychohistory” that predicts human development using historical trends. Perhaps history will evolve into an art – where humans simply pluck at the strings of individual stories and connect the past like notes in a song. Perhaps computers will make these automatically available for public consumption, and historical knowledge will be like phone numbers in 2015: utterly common, absolutely necessary, but entirely forgettable. You have it when you need it.

Michael Whelan's cover for Isaac Asimov's Foundation.

“Then” and “Now” will be much closer in this world. The relationship to the past will seem less like history and more like one long, living memory. The Second World War has resonated strongly in the last two decades partially because its veterans are dying out and sharing their stories – much the same happened in the 1960s with the First World War. Historians wrote the story of their fathers or grandfathers, and likely imbued them with some personal significance. These generational divides will be nonexistent for Robot Historians. All history will be remembered as if it had happened in our lifetime. Even “memory” will be a misnomer as we know it today, since we will no longer combine remembering with forgetting. History will be in its idealized form where anything recorded will be remembered.

New questions might arise as decisions about what’s recorded will have new seriousness. If everything can be recorded, leaving something out will be an incredibly significant act. We will no longer ask about “preserving something for the future,” but wonder about “destroying something for the future.” As powerful as the broad strokes of history are today, imagine when we control it with the precision of a scalpel. Maybe criminals will have their records deleted after execution – removing them from the infinite memory of Robot Historians forever.

So too might Robot Historians forever remember the vastness of human suffering. We will no longer “forget” the cruelties of the past or rank the pain of others as less worthy of recording. “Going down in history” will not be an accomplishment. All history and all voices will be equal. We can only hope that Robot Historians will remind us of our mistakes, and help us avoid repetition. Since everyone will know history, none will be doomed to repeat it.

Let’s look even further into the future now, beyond what even seems possible. What if in some far distant future we develop the capacity to see all past events. Using a Time Viewer, we can see any moment that has happened in the past. Now every event is recorded by virtue of having happened. You can step into a Virtual Reality simulator, and personally witness the signing of the Magna Carta, or the daily life of Aztecs by wandering the streets of Tenochtitlan, or explore the land of the dinosaurs. Human civilization itself, a mere blip on the lifetime of our planet, becomes insignificant compared to the eons of history we can explore – though hopefully it is still the most interesting. The scope of history is now so expansive and inclusive that a distinction between “then” and “now” disappears.

A time portal as imagined on the Star Trek episode, "The City on the Edge of Forever."

This age no doubt spells the end of History. Our Robot Historians can now easily plot the grand trends of human development, the vagaries of individual nuance, and the impact of every decision ever made. “Experiential history” would be a literal term as humans can now actually bear witness to the past. The great movers of history (known and unknown) can be followed from cradle to grave. Family history can be traced in every detail (perhaps in too much detail). The craft of history – building narratives from the past – might become recreating scenes like a television show. The viewer follows history from one epoch to another, following the upheavals of generations or within a single life. There is only one source, the past itself, and perspectives are limited by the viewer rather than our sources.

Of course, these futures could easily take a far different form than what we’ve described here. Ideal worlds where everyone understands the past and takes full advantage of its exploration are unlikely. It is just as likely that the technology described here creates a 1984 dystopia where history is manufactured and concealed rather than an open-access Star Trek utopia.

So what can we learn from this thought exercise?

It presents some useful scenarios for understanding our relationship to history today. Not one of these futures can ever relay the experience of the past as it was lived – we are forever witnesses to it. If the historian conveys in some small way what the past was like, either through their prose or study, and can transfer some part of that experience to their readers, then they have done something that is as unique now as it will be centuries from now. This will forever remain an important element of the historian’s craft.

So too are we always limited by our sources. Even if these restrictions are partially overcome by digital tools in the near future, they will continue to shape our understanding of the past. Only by entirely removing those limits using our Time Viewer to see all of the past can we imagine history radically different than what we know today. As long as we are bound to our sources, we are bound to the same sort of history that historians have practised for generations.

This exercise also reminds us that historians must better understand and embrace digital tools. Not as a trendy addition to our toolbox, but as something that will fundamentally alter the connection between “then” and “now.” Already, programmers have developed algorithms that are replicating historical research. How far away are we from Robot Readers, or Robot Historians? The digital revolution is here and historians must be actively involved in shaping our future relationship with history.

How do you think history will change?